Most of Africa’s fertile land lying

idle, World Bank report says

Updated Wednesday, July 24th 2013 at 23:05 GMT +3

GLANCE FACTS

“Land governance is a proven pathway to

achieving transformational change and impact that will help secure Africa’s future for

the benefit of all its families.”

By Protus Onyango

Africa has the highest poverty rate in the world with 47.5 per cent of the population living below $1.25 (Sh108) a day.

“Despite abundant land and mineral wealth, Africa remains poor,” said Makhtar Diop, World Bank Vice-President for Africa.

He added, “Improving land governance is vital for achieving rapid economic growth and translating it into significantly less poverty and more opportunity for Africans, including women who make up 70 per cent of Africa’s farmers yet are locked out of land ownership due to customary laws,” he said, adding, “The status quo is unacceptable and must change so that all Africans can benefit from their land.”

The report notes that more than 90 per cent of Africa’s rural land is undocumented, making it highly vulnerable to land grabbing and expropriation with poor compensation.

However, based on encouraging evidence from country pilots such as Ghana, Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania and Uganda, the report suggests an action plan that could help revolutionise agricultural production, end land grabbing and eradicate extreme poverty in Africa.

The report suggests that Africa could finally realise the vast development promise of its land over the course of the next decade by championing reforms and investments to document all communal lands and prime lands that are individually owned.

The report says it would cost African countries and their development partners, including the private sector, $4.5 billion over 10 years to scale up policy reforms and investments.

“Improving the performance and productivity of Africa’s agricultural sector is vital for broad-based growth, more jobs, investment and substantially less poverty,” said Jamal Saghir, World Bank Director for Sustainable Development in Africa.

Comments:

mkulima25 July 2013 6:34

PM

johnson, your comment

is on the money, note that california is mostly desert and is the salad basket

of america making it the 5th or 6th largest economy in the world. The signs in

the central valley say "food grows where water flows". This valley, where all

the farming takes place is irrigated by a 500 mile aqueduct that comes from the

sierra nevada mountains. The canal has pumps to push water through where gravity

cannot and control points to regulate water volume. Even the so called arid

areas of kenya in eastern and northeastern are potentially salad baskets of all

of east africa!

Johnson cheruiyot25 July 2013 5:16 AM

It is very true that the issue of food security is still among the

leading threats of many human lives in Africa.As an Agricultural irrigation

engineer such dry places should be incoorporated with modern irrigation this can

even boost not only food security but also can generate income through

export.

Turkana springs to life as hunger and poverty fight gets boost

Farmers tend their farms full of green, blossoming vegetables of every kind, while Safaricom boss was one of those marvelled by the produce from the farms at a makeshift market near Kaikor trading center.

By JOHN NJAGI jnjagi@ke.nationmedia.com

Posted Thursday, July 25 2013 at 21:59

Posted Thursday, July 25 2013 at 21:59

In Summary

- Turkana senator John Munyes says although the people have benefited from the contributions by fellow Kenyans to uplift their livelihoods, challenges persist in accessing markets due to lack of vehicles and smooth road network.

Like a desert that springs to life after a rare spell of rain, Turkana is slowly being transformed bit by bit but on a more permanent basis— thanks to Kenyans for Kenya campaign.

The once dry and hunger-ravaged county now boasts of ambitious irrigation projects funded by cash contributed through the campaign that saw Kenyans contribute Sh1 billion two years ago.

The drive was aimed at helping people of Turkana and other dry areas who were virtually on their death beds following prolonged drought in 2011.

Last week, some of the drivers of the initiative visited the region to witness the small-scale, but no less significant, transformation of a people that previously relied on fleeting livestock trade.

With running water, the locals are now assured that their livestock will not die of thirst, and should bore holes and area under irrigation be increased, pasture could also be assured.

Green houses dotting the county are fast yielding

crops and some families are already minting cash.

Red Cross secretary-general Abbas Gullet says Sh323 million of the funds has been used to dig 12 bore holes in Turkana North constituency to irrigate three massive schemes in Langetulae, Kaikor and Longolemmor villages.

Each of the villages has six green houses where tomatoes, maize, kales, spinach, maize, millet and other crops are grown under drip irrigation.

The rest of the money was used to start similar projects in Moyale, East Pokot and Baringo, where residents perennially suffered drought and hunger due to rain shortages.

“These projects are making a bit of a difference and prove that the tide of famine that leaves these areas with no animals and children on their deathbed can be turned around to, not only ensure the residents have food on the table, but also money in their pockets,” says Mr Gullet.

Dozens of pastoralists-cum-farmers are happy to harvest tomatoes, fresh spinach and cabbages that are sold at makeshift markets— a rare spectacle in a land that is usually dry for the most part of the year.

Despite receding vegetation in the surrounding land, the residents are reassured that with water and vegetables in plenty, there will be no repeat of the hunger and desperation of past years.

Would reduce

Turkana Governor Josephat Nanok says the availability of water would reduce nomadic movement of the pastoralists, and help the county government build permanent schools and health centres to serve them.

His government, he says, will set aside Sh3.5 billion to expand the irrigation projects started under the Kenyans for Kenya initiative to cover more areas, and improve existing infrastructure such as roads to ease farmers’ access to markets.

“Kenyans who contributed money towards assisting the people of Turkana have showed us that resources can be put to use to change the lives of the people here,” says Mr Nanok.

“Our county government will pick up from there and move the projects forward to ensure hunger is made history.”

Safaricom chief executive Bob Collymore, one of the corporate sponsors of the project alongside media owners and ordinary Kenyans, says through generous donations, thousands of people from some of the driest parts of the country are not only food secure but have a steady source of income from sale of vegetables.

“These projects have helped at least 15,000 people, with each family earning at least Sh4,000 per day on market days and that will completely change the fortunes of a people that were on the verge of desperation,” he notes.

Now that there is agro-pastoralism taking place, he says, the county and central governments should settle them and ensure they are provided with essential services such as health and education.

Turkana senator John Munyes says although the people have benefited from the contributions by fellow Kenyans to uplift their livelihoods, challenges persist in accessing markets due to lack of vehicles and smooth road network.

He says the county government will ensure the farmers form cooperatives so as to buy vehicles that will assist them transport the produce to markets.

Funds devolved to the county, he adds, will be used to build a road connecting the villages to Lodwar Town— the seat of the county’s

administration.

Although it is less than 50 kilometres from villages, it takes about two hours on average to drive to the town due to poor (read lack of) roads.

Farmers find it hard to access the town’s markets, leading to loss of harvest and income.

Mr Eyanae Elim, a moran who has taken up farming to supplement what he earns from the livestock trade, says the size of land in the greenhouse allocated to him is too small and is hardly profitable.

The greenhouses are the size of a basketball court, and are shared between two households.

The greenhouses are the size of a basketball court, and are shared between two households.

Those owning the parcels wish they could be expanded to generate more income.

Plots are small

“We thank them (Kenyans) for starting this initiative but currently, the plots are too small and it would be more viable to have an individual farm the whole greenhouse rather than sharing between two people,” he says.

Farmers mostly sell their produce to civil servants and NGO staff in the area, which relieves them of the transportation cost to Lodwar and Kaikor market, where they would otherwise sell the produce on a market day.

Another farmer, Ms Lobunon Myan from Kanyatulae Village, says transport to the market is very expensive, and that planting is marked by delays due to lack of seeds.

Pests are also the norm as pesticides are not being supplied by those tasked with ensuring the projects runs smoothly.

However, there are big hopes as their success is being replicated in other parts of the county. Schools have adopted it, and are teaching students how to fight poverty and hunger.

The head teacher of Kaikor Primary School, Mr Paul Losikiria, says his school has started a greenhouse that supplements relief food from the school feeding programme.

Undergone training

“Two of our teachers have undergone training and are now teaching the pupils to farm,” he says.

“The harvest has been supplementing our school feeding programme but we are looking for ways to expand the irrigation so as to create a source of income,” he adds.

The projects have shown the tremendous potential of the region to become food secure if funds are channelled to that cause.

With the counties receiving billions under devolution, and with new-found oil wealth in Turkana, there is no telling the amount of transformation and economic empowerment of the marginalised groups should the wealth be put to prudent use.

Despite the remarkable progress, the lives of the people of Turkana — a region covering 77,000 square kilometres with an estimated 855,399 population — are not yet out of the woods.

The irrigation scheme covering three villages in one constituency and benefiting a paltry 15,000 families is too little. More needs to be done by the national and county governments.

Small farmers can make the most of Africa's land

January 18, 2012 - FSE, FSI Stanford News

By Kate Johnson

In Kenya, 11 million people suffer from malnourishment. Twenty percent of children younger than five are underweight, and nearly one in three are below normal height. In a typical day, the average Kenyan consumes barely half as many calories as the average American.

But Kenya – and other underfed countries throughout Sub-Saharan Africa – have more than enough land to grow the food needed for their hungry populations.

The juxtaposition of food deprivation and land abundance boils down to a failure of national agriculture policies, says Thom Jayne, professor of international development at Michigan State University. Governments haven’t helped small farmers acquire rights to uncultivated land or use the land they own more productively, he said.

Speaking earlier this month at a symposium organized by the Center on Food Security and the Environment, Jayne said lifting African farmers out of poverty will require a new development approach.

The focus, he said, should be on increasing smallholder output and putting idle land to work in the hands of the rural poor.

Much of Sub-Saharan Africa’s fertile land, Jayne explained, falls under the ownership of state governments or wealthy investors who leave large tracts of land unplanted.

Meanwhile, population density in many rural areas exceeds the estimated carrying capacity for rainfed agriculture – approximately 500 persons per square kilometer, according to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization. Above this density threshold, farm sizes become so small, farming becomes economically unsustainable.

“As farm size shrinks, it’s increasingly difficult to produce a surplus,” Jayne said. “As it’s difficult to produce a surplus, it becomes difficult to finance investments in fertilizer and other inputs that could help you intensify.”

Agricultural development policies, Jayne said, have exacerbated these problems. One Zambian fertilizer subsidy program, for example, delivered support payments to over 50 percent of farms greater than five hectares in size – but only reached 14 percent of farmers whose holdings measured one hectare or smaller.

“This was a poverty reduction program that was targeted to large farms,” Jayne said. “Where’re the allocations to R&D appropriate to one hectare farms, tsetse fly control, vet services, all the things that are going to make that one hectare farm more productive?”

He stressed that investments in small farms could reduce poverty.

“Fifty to seventy percent of the population in these countries is engaged in agriculture,” he said. “There aren’t very many levers to reduce poverty and get growth processes going except to focus on the activities that that fifty to seventy percent are primarily engaged in.”

Smallholder-based growth strategies delivered stunning results in Green Revolution-era India – while large-farm strategies in Latin American countries have largely failed to alleviate rural poverty, he said.

Symposium commentator Byerlee, a rural policy expert and former lead economist for the World Bank, agreed with Jayne. In particular, Byerlee expressed skepticism about the benefit of large land investments by foreign agricultural interests.

“The social impacts aren’t going to be very much,” he said of the large-scale mechanized farming operations favored by foreign investors.

“They don’t create many jobs,” he said. “That’s really what we should be focusing on in terms of poverty reduction – job creation.”

Byerlee also stressed the need to formalize Sub-Saharan Africa’s land tenure systems. Currently, he said, about eighty percent of Africa’s land is titled informally under “customary” rights.

“When you have this population pressure, and on top of that you have commercial pressures coming in from investors, this system is just not going to stand up,” he said. “If you had better functioning land markets, it could reduce the transaction costs for investors, allow smallholders to access land, and provide an exit strategy for people at the bottom end.”

Jayne suggested reforms and new policies should include mechanisms to help small farmers gain access to unused fertile land. He called for comprehensive audits of land resources in Sub-Saharan African nations, a tax on uncultivated arable acreage, and a transparent public auction to distribute idle state lands to small farmers.

Additionally, he said, governments can help by improving infrastructure in remote rural areas and clearing fertile land of pests – such as tsetse flies – that threaten crops and human health.

But whatever particular policies they choose to pursue, Jayne said, African governments cannot afford to ignore the problems associated with inequitable land distribution and low smallholder agricultural productivity and. Failure to implement broad-based, smallholder-focused growth strategies will result in “major missed opportunities to reduce poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa,” he said.

This was the seventh talk in FSE's Global Food Policy and Food Security Symposium Series.

But Kenya – and other underfed countries throughout Sub-Saharan Africa – have more than enough land to grow the food needed for their hungry populations.

The juxtaposition of food deprivation and land abundance boils down to a failure of national agriculture policies, says Thom Jayne, professor of international development at Michigan State University. Governments haven’t helped small farmers acquire rights to uncultivated land or use the land they own more productively, he said.

Speaking earlier this month at a symposium organized by the Center on Food Security and the Environment, Jayne said lifting African farmers out of poverty will require a new development approach.

The focus, he said, should be on increasing smallholder output and putting idle land to work in the hands of the rural poor.

Much of Sub-Saharan Africa’s fertile land, Jayne explained, falls under the ownership of state governments or wealthy investors who leave large tracts of land unplanted.

Meanwhile, population density in many rural areas exceeds the estimated carrying capacity for rainfed agriculture – approximately 500 persons per square kilometer, according to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization. Above this density threshold, farm sizes become so small, farming becomes economically unsustainable.

“As farm size shrinks, it’s increasingly difficult to produce a surplus,” Jayne said. “As it’s difficult to produce a surplus, it becomes difficult to finance investments in fertilizer and other inputs that could help you intensify.”

Agricultural development policies, Jayne said, have exacerbated these problems. One Zambian fertilizer subsidy program, for example, delivered support payments to over 50 percent of farms greater than five hectares in size – but only reached 14 percent of farmers whose holdings measured one hectare or smaller.

“This was a poverty reduction program that was targeted to large farms,” Jayne said. “Where’re the allocations to R&D appropriate to one hectare farms, tsetse fly control, vet services, all the things that are going to make that one hectare farm more productive?”

He stressed that investments in small farms could reduce poverty.

“Fifty to seventy percent of the population in these countries is engaged in agriculture,” he said. “There aren’t very many levers to reduce poverty and get growth processes going except to focus on the activities that that fifty to seventy percent are primarily engaged in.”

Smallholder-based growth strategies delivered stunning results in Green Revolution-era India – while large-farm strategies in Latin American countries have largely failed to alleviate rural poverty, he said.

Symposium commentator Byerlee, a rural policy expert and former lead economist for the World Bank, agreed with Jayne. In particular, Byerlee expressed skepticism about the benefit of large land investments by foreign agricultural interests.

“The social impacts aren’t going to be very much,” he said of the large-scale mechanized farming operations favored by foreign investors.

“They don’t create many jobs,” he said. “That’s really what we should be focusing on in terms of poverty reduction – job creation.”

Byerlee also stressed the need to formalize Sub-Saharan Africa’s land tenure systems. Currently, he said, about eighty percent of Africa’s land is titled informally under “customary” rights.

“When you have this population pressure, and on top of that you have commercial pressures coming in from investors, this system is just not going to stand up,” he said. “If you had better functioning land markets, it could reduce the transaction costs for investors, allow smallholders to access land, and provide an exit strategy for people at the bottom end.”

Jayne suggested reforms and new policies should include mechanisms to help small farmers gain access to unused fertile land. He called for comprehensive audits of land resources in Sub-Saharan African nations, a tax on uncultivated arable acreage, and a transparent public auction to distribute idle state lands to small farmers.

Additionally, he said, governments can help by improving infrastructure in remote rural areas and clearing fertile land of pests – such as tsetse flies – that threaten crops and human health.

But whatever particular policies they choose to pursue, Jayne said, African governments cannot afford to ignore the problems associated with inequitable land distribution and low smallholder agricultural productivity and. Failure to implement broad-based, smallholder-focused growth strategies will result in “major missed opportunities to reduce poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa,” he said.

This was the seventh talk in FSE's Global Food Policy and Food Security Symposium Series.

Land Grabs – There Is No Idle Land In Africa

June 11, 2011

Source:

Modern Ghana

By Pan-Africanist International

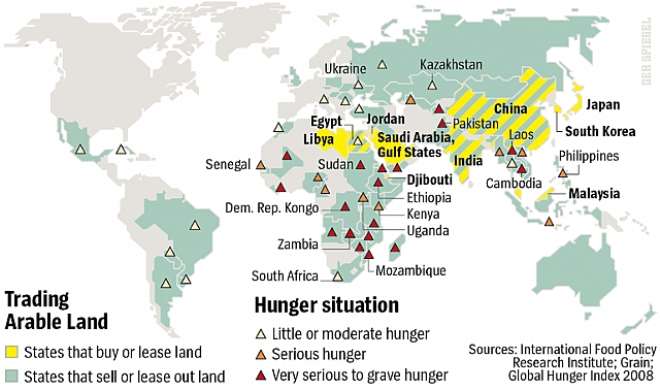

Africa land grab and hunger map

Harvard and other major American universities are working through British hedge funds and European financial speculators to buy or lease vast areas of African farmland in deals, some of which may force many thousands of people off their land …

… No one should believe that these investors are there to feed starving Africans, create jobs or improve food security …

Much of the money is said to be channelled through London-based Emergent asset management, which runs one of Africa's largest land acquisition funds, run by former JP Morgan and Goldman Sachs currency dealers.

… Emergent's clients in the US may have invested up to $500m in some of the most fertile land in the expectation of making 25% returns.

“These agreements – many of which could be in place for 99 years – do not mean progress for local people and will not lead to food in their stomachs. These deals lead only to dollars in the pockets of corrupt leaders and foreign investors.”

“The scale of the land deals being struck is shocking”, said Mittal. “The conversion of African small farms and forests into a natural-asset-based, high-return investment strategy can drive up food prices and increase the risks of climate change.

Research by the World Bank and others suggests that nearly 60m hectares – an area the size of France – has been bought or leased by foreign companies in Africa in the past three years.

“Most of these deals are characterised by a lack of transparency, despite the profound implications posed by the consolidation of control over global food markets and agricultural resources by financial firms,” says the report.

“We have seen cases of speculators taking over agricultural land while small farmers, viewed as squatters, are forcibly removed with no compensation,” said Frederic Mousseau, policy director at Oakland, said: “This is creating insecurity in the global food system that could be a much bigger threat to global security than terrorism. More than one billion people around the world are living with hunger. The majority of the world's poor still depend on small farms for their livelihoods, and speculators are taking these away while promising progress that never happens.” (The Guardian)

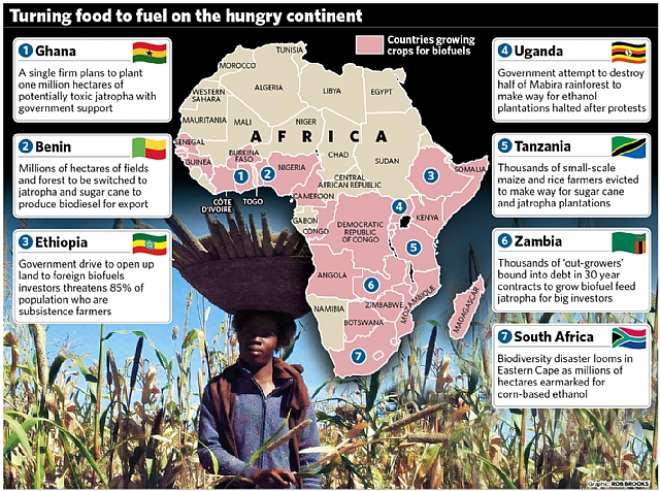

Africa biofuels land grab map

THIS NEW scramble for African land has visited a multitude of problems on ordinary Africans and set the stage for ecological crisis and widespread hunger.As many critics have pointed out, African governments have falsely claimed that land available for sale is unused. As journalist Joan Baxter writes:

Some defend the investors' acquisition of land in their countries, saying it is “virgin” or “under-utilized” or “uncultivated” or “degraded” land…This suggests they know precious little about the importance of fallows and the resilience and diversity of agroforestry systems, or about sustainable agriculture and the knowledge base of their own farmers.

Communal land, small farmers and even entire villages are often displaced in the drive for land purchases. The Oakland Institute think-tank released a report on the African land grab, which points out:

Experts in the field, however, affirm that there is no such thing as idle land in…Africa…Countless studies have shown that competition for grazing land and access to water bodies are the two most important sources of inter-communal conflict in [areas] populated by pastoralists.

According to Michael Taylor, a policy specialist at the International Land Coalition, “If land in Africa hasn't been planted, it's probably for a reason. Maybe it's used to graze livestock or deliberately left fallow to prevent nutrient depletion and erosion. Anybody who has seen these areas identified as unused understands that there is no land…that has no owners and users.”

In other words, as activist Vandana Shiva puts it, “We are seeing dispossession on a massive scale. It means less food is available and local people will have less. There will be more conflict and political instability and cultures will be uprooted. The small farmers of Africa are the basis of food security. The food availability of the planet will decline.”

In fact, because much of its food is produced for export, sub-Saharan Africa is the only region in the world where per capita food production has been declining, with the number of people that are chronically hungry and undernourished currently estimated at more than 265 million.

Nations with large amounts of land sold or leased to foreign owners are often food importers, and their inability to feed their own populations is exacerbated by the displacement of food producers who grow for local use. The UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) reports that Africa has lost 20 percent of its capacity to feed itself over the past four decades. Ethiopia alone has 13 million people in immediate need of food assistance, yet its government has put over 7 million acres of land up for sale.

And worsening hunger is still to come. …

Large-scale land acquisition poses massive ecological threats to the African environment. The dangers are numerous: hazardous pesticides and fertilizers cause water contamination from their runoff, the introduction of genetically modified seeds and other problems. Land previously left to lie fallow is now threatened with overuse from intensified agricultural development, a trend further exacerbated by speculative investment and the drive for short-term profits.

Yet deals transferring vast tracts of land are typically taking place far removed from local farmers and villagers with virtually no accountability. As Khadija Sharife writes on the Pambazuka Web site:

The deals involving these concessions are often cloaked in secrecy, but African business has learned that they are usually characterized by allowing free access to water, repatriation of profits, tax exemptions and the ability for investors to acquire land at no cost whatsoever, with little or no restriction on the volume of food exported or its intended use, in return for a loose promise to develop infrastructure and markets…

In many cases, farmers and pastoralists have worked this land for centuries. However, governments are claiming this land is idle in order to more easily sell or lease it to private investors. (New African Land Grab)

I found this a particularly telling passage from (Mis)investment in Agriculture: The Role of the International Finance Corporation In Global Land Grabs (PDF) a publication of the Oakland Institute.

Proponents of the land deals will dismiss my concerns and claim that this type of foreign investment will benefit the local people by providing jobs and creating infrastructure. They will also say that the land being offered is “unused.” These are hollow arguments. Investors have been quoted as saying they will employ 10,000 people and use high-tech, high-production farming techniques. The two promises are completely incongruous. As a farmer, I can tell you that high-tech, high production devices are appealing precisely because they reduce labor. Investors will not hire significant numbers of people and simultaneously scale-up their production techniques. And if they choose the former, they are likely to create low-paying jobs and poor working conditions. I may be making assumptions, but they are based on history—a history dating back to colonialism and one that has exploited both natural resources and people.

Particularly disconcerting is the notion that the “available” land is “unused.” This land is in countries with the highest rates of malnutrition on the only continent that produces less food per capita than it did a decade ago. In most cases, this land has a real purpose: it may support corridors for pastoralists; provide fallow space for soil regeneration; provide access to limited water sources; be reserved for future generations; or enable local farmers to increase production. The fact that rich and emerging economies do not have or do not respect pastoralists or use land for age-old customs does not mean we have a right to label this land unused.

Some defend the investors' acquisition of land in their countries, saying it is “virgin” or “under-utilized” or “uncultivated” or “degraded” land…This suggests they know precious little about the importance of fallows and the resilience and diversity of agroforestry systems, or about sustainable agriculture and the knowledge base of their own farmers.

Communal land, small farmers and even entire villages are often displaced in the drive for land purchases. The Oakland Institute think-tank released a report on the African land grab, which points out:

Experts in the field, however, affirm that there is no such thing as idle land in…Africa…Countless studies have shown that competition for grazing land and access to water bodies are the two most important sources of inter-communal conflict in [areas] populated by pastoralists.

According to Michael Taylor, a policy specialist at the International Land Coalition, “If land in Africa hasn't been planted, it's probably for a reason. Maybe it's used to graze livestock or deliberately left fallow to prevent nutrient depletion and erosion. Anybody who has seen these areas identified as unused understands that there is no land…that has no owners and users.”

In other words, as activist Vandana Shiva puts it, “We are seeing dispossession on a massive scale. It means less food is available and local people will have less. There will be more conflict and political instability and cultures will be uprooted. The small farmers of Africa are the basis of food security. The food availability of the planet will decline.”

In fact, because much of its food is produced for export, sub-Saharan Africa is the only region in the world where per capita food production has been declining, with the number of people that are chronically hungry and undernourished currently estimated at more than 265 million.

Nations with large amounts of land sold or leased to foreign owners are often food importers, and their inability to feed their own populations is exacerbated by the displacement of food producers who grow for local use. The UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) reports that Africa has lost 20 percent of its capacity to feed itself over the past four decades. Ethiopia alone has 13 million people in immediate need of food assistance, yet its government has put over 7 million acres of land up for sale.

And worsening hunger is still to come. …

Large-scale land acquisition poses massive ecological threats to the African environment. The dangers are numerous: hazardous pesticides and fertilizers cause water contamination from their runoff, the introduction of genetically modified seeds and other problems. Land previously left to lie fallow is now threatened with overuse from intensified agricultural development, a trend further exacerbated by speculative investment and the drive for short-term profits.

Yet deals transferring vast tracts of land are typically taking place far removed from local farmers and villagers with virtually no accountability. As Khadija Sharife writes on the Pambazuka Web site:

The deals involving these concessions are often cloaked in secrecy, but African business has learned that they are usually characterized by allowing free access to water, repatriation of profits, tax exemptions and the ability for investors to acquire land at no cost whatsoever, with little or no restriction on the volume of food exported or its intended use, in return for a loose promise to develop infrastructure and markets…

In many cases, farmers and pastoralists have worked this land for centuries. However, governments are claiming this land is idle in order to more easily sell or lease it to private investors. (New African Land Grab)

I found this a particularly telling passage from (Mis)investment in Agriculture: The Role of the International Finance Corporation In Global Land Grabs (PDF) a publication of the Oakland Institute.

Proponents of the land deals will dismiss my concerns and claim that this type of foreign investment will benefit the local people by providing jobs and creating infrastructure. They will also say that the land being offered is “unused.” These are hollow arguments. Investors have been quoted as saying they will employ 10,000 people and use high-tech, high-production farming techniques. The two promises are completely incongruous. As a farmer, I can tell you that high-tech, high production devices are appealing precisely because they reduce labor. Investors will not hire significant numbers of people and simultaneously scale-up their production techniques. And if they choose the former, they are likely to create low-paying jobs and poor working conditions. I may be making assumptions, but they are based on history—a history dating back to colonialism and one that has exploited both natural resources and people.

Particularly disconcerting is the notion that the “available” land is “unused.” This land is in countries with the highest rates of malnutrition on the only continent that produces less food per capita than it did a decade ago. In most cases, this land has a real purpose: it may support corridors for pastoralists; provide fallow space for soil regeneration; provide access to limited water sources; be reserved for future generations; or enable local farmers to increase production. The fact that rich and emerging economies do not have or do not respect pastoralists or use land for age-old customs does not mean we have a right to label this land unused.