Good People,

All these information are clear indication that Kagame is fully involved

in distabilization of DRC through M23. Kagame must be taken to task

at the ICC Hague as He has a case to answer.

Why would Kagame ask America to kill Congo rebel leader ?

Is it for cover up??? Does Kagame know something he does

not want the world to know.....???

Push for the truth people.......There is more here and it is

unacceptable......

Judy Miriga

Diaspora Spokesperson

Executive Director

Confederation Council Foundation for Africa Inc.,

USA

http://socioeconomicforum50.blogspot.com

Diaspora Spokesperson

Executive Director

Confederation Council Foundation for Africa Inc.,

USA

http://socioeconomicforum50.blogspot.com

1) ALTHOUGH......... !!!

JEB HENSARLING, TX , CHAIRMAN

United States House of Representatives

Committee on Financial Services 2129 Rayburn House Office Building Washington, D.C. 20515

MAXINE WATERS, CA, RANKING MEMBER

M E M O R A N D U M

To:

Members of the Committee on Financial Services

From:

FSC Majority Committee Staff

Date:

May 16, 2013

Subject:

May 21, 2013, Monetary Policy and Trade Subcommittee Hearing on "The Unintended Consequences of Dodd-Frank’s Conflict Minerals Provision".

The Subcommittee on Monetary Policy and Trade will hold a hearing on "The Unintended Consequences of Dodd-Frank’s Conflict Minerals Provision" at 2:00 p.m. on Tuesday, May 21, 2013, in Room 2128 of the Rayburn House Office Building. This will be a one-panel hearing with the following witnesses:

• David Aronson, Freelance Writer, Editor of www.congoresources.org

• Mvemba Dizolele, Peter Duignan Distinguished Visiting Fellow, Hoover Institution

• Rick Goss, Senior Vice President of Environment and Sustainability, Information Technology Industry Council

• Sophia Pickles, Policy Advisor, Global Witness

Background

Ever since it gained its independence in 1960, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) has been in a state of civil war. In 2000, the United Nations Group of Experts linked the Congolese civil war to the mineral trade. Tin, tantalum, tungsten, and gold—which are used to manufacture everyday goods such as pens, USB drives, buttons, and food containers—are mined in areas of the eastern DRC that the Congolese army and armed militias are fighting to control. The factions use proceeds from mineral sales to buy weapons. Some have argued that banning the use of minerals mined in or near the DRC or discouraging companies from using such minerals by "naming and shaming" them might deny rebel militias a source of funding and end the conflict.

Section 1502 of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (P.L. 111-203) is one such effort to discourage companies from using minerals mined in the DRC. Section 1502 requires the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to promulgate rules for public companies requiring them to disclose their use of minerals that originated in the DRC, which Section 1502 defines to be "conflict minerals." Public companies must comply with Section 1502’s disclosure requirements when these minerals are necessary to the functionality or production of a product. If companies cannot verify that the minerals they use did not originate in the DRC, Section 1502 requires them to (1) exercise due diligence on the source and chain of custody of these minerals; (2) hire an independent third party to audit the due diligence measures; and (3) report to the SEC on the due diligence measures they undertook and their auditor’s assessment of those measures.

Hearing:

Hearing entitled "The Unintended Consequences of Dodd-Frank's Conflict Minerals Provision"

Tuesday, May 21, 2013 2:00 PM in 2128 Rayburn HOB

Monetary Policy and Trade

Tuesday, May 21, 2013 2:00 PM in 2128 Rayburn HOB

Monetary Policy and Trade

Click here for the Archived Webcast of this hearing.

Click here for the Committee Memorandum.

Witness List

Mr. David Aronson, Freelance Writer, Editor of www.congoresources.org

- Mr. Mvemba Dizolele, Peter Duignan Distinguished Visiting Fellow, Hoover Institution

- Mr. Rick Goss, Senior Vice President of Environment and Sustainability, Information Technology Industry Council

- Ms. Sophia Pickles, Policy Advisor, Global Witness

2) This becomes a concern........!!!

$625,000 Worth Gold Shipment Got Lost At Miami Airport

Published on May 17, 2013

A shipment of gold valued at $625,000 vanished in a suspected heist after arriving in Miami on an American Airlines flight, authorities announced Thursday.

A police report says the gold, which arrived in a box, was brought on the flight from Guayaquil, Ecuador to the Miami International Airport early Tuesday, WSVN reports.

The plane's cargo was unloaded by five crew members, but the box containing the gold disappeared after apparently being loaded onto a motorized luggage cart or tug, the report said.

The cart was found in front of a gate of the same terminal were the flight from Ecuador was unloaded, about an hour after workers emptied the cargo hold, but without the box containing the gold.

The police incident report did not say who owned the gold or what its final destination was and an American Airlines security official at the airport declined to comment to Reuters on the case, saying only that it was being investigated by the FBI.

"The FBI is aware of the situation," FBI spokesman Michael Leverock told Reuters in an email.

Miami International serves as a major trans-shipment point for large quantities of gold produced in South America and exported primarily to Switzerland for refining.

The city has seen the trans-shipment of gold rise sharply in recent years as investors have turned to gold and its price has risen.

Gold is Miami's No. 1 import valued at almost $8 billion last year, mostly from Mexico and Colombia, and almost all destined for Switzerland, according to World City, a Miami-based publication that tracks trade data.

A police report says the gold, which arrived in a box, was brought on the flight from Guayaquil, Ecuador to the Miami International Airport early Tuesday, WSVN reports.

The plane's cargo was unloaded by five crew members, but the box containing the gold disappeared after apparently being loaded onto a motorized luggage cart or tug, the report said.

The cart was found in front of a gate of the same terminal were the flight from Ecuador was unloaded, about an hour after workers emptied the cargo hold, but without the box containing the gold.

The police incident report did not say who owned the gold or what its final destination was and an American Airlines security official at the airport declined to comment to Reuters on the case, saying only that it was being investigated by the FBI.

"The FBI is aware of the situation," FBI spokesman Michael Leverock told Reuters in an email.

Miami International serves as a major trans-shipment point for large quantities of gold produced in South America and exported primarily to Switzerland for refining.

The city has seen the trans-shipment of gold rise sharply in recent years as investors have turned to gold and its price has risen.

Gold is Miami's No. 1 import valued at almost $8 billion last year, mostly from Mexico and Colombia, and almost all destined for Switzerland, according to World City, a Miami-based publication that tracks trade data.

3) And Now This .........!!!!

Paul Kagame: I asked America to kill Congo rebel leader with drone

In an exclusive interview with Chris McGreal in Kigali, Rwanda's president denies backing an accused Congolese war criminal and says challenge to senior US official proves his innocence

--- On Thu, 5/23/13, Augustine Rukoma

Msimtetea Kabila hata kidogo, Kagame kasema kweli, M23 ni nzi hawashambulii

wala kupanga vita. Wanajeshi wa Kabila wakisikia hata baruti wanakimbia.

Jeshi gani hili la woga. Ile nchi inatakiwa reformation kubwa ndio

inayowavutia mainzi kama M23 kufanya wanachotaka.

From: A S Kivamwo <kivamwo@yahoo.com>

To: mabadilikotanzania@googlegroups.com

Sent: Wednesday, May 22, 2013 5:22 AM

Subject: Re: [Mabadiliko] Paul Kagame: I asked America to kill Congo

- The Observer, Saturday 18 May 2013

- Jump to comments (46)

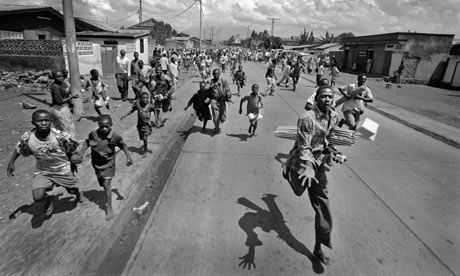

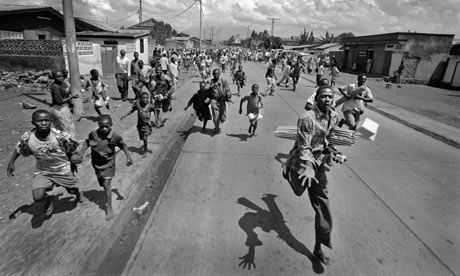

A new M23 recruit demonstrates his martial arts skills in the Democratic Republic of the Congo last week. Rwanda denies aiding them. Photograph: James Akena/Reuters

Rwanda's president, Paul Kagame, has rejected accusations from Washington that he was supporting a rebel leader and accused war criminal in the Democratic Republic of the Congo by challenging a senior US official to send a drone to kill the wanted man.

In an interview with the Observer Magazine, Kagame said that on a visit to Washington in March he came under pressure from the US assistant secretary of state for Africa, Johnnie Carson, to arrest Bosco Ntaganda, leader of the M23 rebels, who was wanted by the international criminal court (ICC). The US administration was increasing pressure on Kagame following a UN report claiming to have uncovered evidence showing that the Rwandan military provided weapons and other support to Ntaganda, whose forces briefly seized control of the region's main city, Goma.

"I told him: 'Assistant secretary of state, you support [the UN peacekeeping force] in the Congo. Such a big force, so much money. Have you failed to use that force to arrest whoever you want to arrest in Congo? Now you are turning to me, you are turning to Rwanda?'" he said. "I said that, since you are used to sending drones and gunning people down, why don't you send a drone and get rid of him and stop this nonsense? And he just laughed. I told him: 'I'm serious'."

Kagame said that, after he returned to Rwanda, Carson kept up the pressure with a letter demanding that he act against Ntaganda. Days later, the M23 leader appeared at the US embassy in Rwanda's capital, Kigali, saying that he wanted to surrender to the ICC. He was transferred to The Hague. The Rwandan leadership denies any prior knowledge of Ntaganda's decision to hand himself over. It suggests he was facing a rebellion within M23 and feared for his safety.

But Kagame's confrontation with Carson reflects how much relationships with even close allies have deteriorated over allegations that Rwanda continues to play a part in the bloodletting in Congo. The US and Britain, Rwanda's largest bilateral aid donors, withheld financial assistance, as did the EU, prompting accusations of betrayal by Rwandan officials. The political impact added impetus to a government campaign to condition the population to become more self-reliant.

Kagame is angered by the moves and criticisms of his human rights record in Rwanda, including allegations that he blocks opponents by misusing laws banning hate speech to accuse them of promoting genocide and suppresses press criticism. The Rwandan president is also embittered that countries, led by the US and UK, that blocked intervention to stop the 1994 genocide, and France which sided with the Hutu extremist regime that led the killings, are now judging him on human rights.

"We don't live our lives or we don't deal with our affairs more from the dictates from outside than from the dictates of our own situation and conditions," Kagame said. "The outside viewpoint, sometimes you don't know what it is. It keeps changing. They tell you they want you to respect this or fight this and you are doing it and they say you're not doing it the right way. They keep shifting goalposts and interpreting things about us or what we are doing to suit the moment."

He is agitated about what he sees as Rwanda being held responsible for all the ills of Congo, when Kigali's military intervention began in 1996 to clear out Hutu extremists using UN-funded refugee camps for raids to murder Tutsis. Kagame said that Rwanda was not responsible for the situation after decades of western colonisation and backing for the Mobutu dictatorship.

The Rwandan leader denies supporting M23 and said he has been falsely accused because Congo's president, Joseph Kabila, needs someone to blame because his army cannot fight. "To defeat these fellows doesn't take bravery because they don't go to fight. They just hear bullets and are on the loose running anywhere, looting, raping and doing anything. That's what happened," he said.

"President Kabila and the government had made statements about how this issue is going to be contained. They had to look for an explanation for how they were being defeated. They said we are not fighting [Ntaganda], we're actually fighting Rwanda."

--- On Thu, 5/23/13, Augustine Rukoma

From: Augustine Rukoma

Subject: Re: [Mabadiliko] Paul Kagame: I asked America to kill Congo rebel leader with drone

To: mabadilikotanzania@googlegroups.com

Date: Thursday, May 23, 2013, 3:07 AM

Subject: Re: [Mabadiliko] Paul Kagame: I asked America to kill Congo rebel leader with drone

To: mabadilikotanzania@googlegroups.com

Date: Thursday, May 23, 2013, 3:07 AM

M23 ni wanyarwanda,wala si banyamulenge. Kongo hii angepewa jk sasa

hivi rais angekuwa bizima karaa, afrika maliasili badala ya kutusaidia

inatuponza

On 5/22/13, Lemburis Kivuyo <lembu.kivuyo@gmail.com> wrote:

hivi rais angekuwa bizima karaa, afrika maliasili badala ya kutusaidia

inatuponza

On 5/22/13, Lemburis Kivuyo <lembu.kivuyo@gmail.com> wrote:

Msimtetea Kabila hata kidogo, Kagame kasema kweli, M23 ni nzi hawashambulii

wala kupanga vita. Wanajeshi wa Kabila wakisikia hata baruti wanakimbia.

Jeshi gani hili la woga. Ile nchi inatakiwa reformation kubwa ndio

inayowavutia mainzi kama M23 kufanya wanachotaka.

Niliwahi kusema huyu kijana ni ubishoo tu kuongoza nchi hata kijiji hawezi

Real Change for Real Development,

Lemburis Kivuyo

+255654650100 - Website: www. <http://www.infocomcenter.com/>kivuyo.com,

+255654650100 - Website: www. <http://www.infocomcenter.com/>kivuyo.com,

On 22 May 2013 17:16, A S Kivamwo <kivamwo@yahoo.com> wrote:

Haa ha ha! Heche umenifanya nicheke! Lakini kweli Kabila naye

anatuaibisha...yeye kila siku kupigwa na kila uasi! Lakini Kagame

kaifafanua vizuri. Kasema kuwa huhitaji kutumia nguvu nyingi kuyashinda

majeshi ya DRC. Wewe ni kupiga mzinga mmoja tu juu hapohapo yanatawanyika

kuelekea nyuma na kupora na kubaka. So Kabila hana jeshi ana makanjanja

tu

anatuaibisha...yeye kila siku kupigwa na kila uasi! Lakini Kagame

kaifafanua vizuri. Kasema kuwa huhitaji kutumia nguvu nyingi kuyashinda

majeshi ya DRC. Wewe ni kupiga mzinga mmoja tu juu hapohapo yanatawanyika

kuelekea nyuma na kupora na kubaka. So Kabila hana jeshi ana makanjanja

tu

On Wed, May 22, 2013 8:36 AM EDT heche suguta wrote:

Kabila aekaa madarakani tangu 2001 mpaka leo hawezi kuua hata nzi tu,

jamaa lile kumbe bure kabisaa

jamaa lile kumbe bure kabisaa

From: A S Kivamwo <kivamwo@yahoo.com>

To: mabadilikotanzania@googlegroups.com

Sent: Wednesday, May 22, 2013 5:22 AM

Subject: Re: [Mabadiliko] Paul Kagame: I asked America to kill Congo

rebel leader with drone muganda bwana?! kwani hao waasi ni wa wapi kama

hawajatoka kwenye jeshi

la kabila? pili tangu kabila mdogo aingie madarakani lini amepata amani

na

akatulia? miaka yote ni vita tu huko east ambazo penda usipende vina

mikono

ya watu wa nje. usimlaumu saana ki hivo. mbona wewe unavaa suti?

la kabila? pili tangu kabila mdogo aingie madarakani lini amepata amani

na

akatulia? miaka yote ni vita tu huko east ambazo penda usipende vina

mikono

ya watu wa nje. usimlaumu saana ki hivo. mbona wewe unavaa suti?

On Wed, May 22, 2013 7:29 AM EDT Emmanuel Muganda wrote:

Hivi Kabila miaka yote hii amekuwa mamlakani amefanya nini kujenga

jeshi?

Yeye ni kuvaa suti tu?

em

Hivi Kabila miaka yote hii amekuwa mamlakani amefanya nini kujenga

jeshi?

Yeye ni kuvaa suti tu?

em

On Wed, May 22, 2013 at 1:49 AM, Augustine Rukoma <arukoma66@gmail.com

wrote:

wrote:

Aka nako ni ka m7 kengine uihuni mtupu

On 5/22/13, shedrack maximilian <shedrack_maximilian@yahoo.co.uk>

wrote:

Very interssting -Thinks its logical ...Congolease never stands as

gentlemen to defend themselves, read this..... 'The Rwandan leader

denies

supporting M23 and said he has been falsely accused because Congo's

president, Joseph Kabila, needs someone to blame because his army

cannot

fight. "To defeat these fellows doesn't take bravery because they

don't

go

to fight. They just hear bullets and are on the loose running

anywhere,

looting, raping and doing anything. That's what happened," he said'

wrote:

Very interssting -Thinks its logical ...Congolease never stands as

gentlemen to defend themselves, read this..... 'The Rwandan leader

denies

supporting M23 and said he has been falsely accused because Congo's

president, Joseph Kabila, needs someone to blame because his army

cannot

fight. "To defeat these fellows doesn't take bravery because they

don't

go

to fight. They just hear bullets and are on the loose running

anywhere,

looting, raping and doing anything. That's what happened," he said'

--- On Wed, 5/22/13, Lutgard Kokulinda Kagaruki

From: Lutgard Kokulinda Kagaruki

Subject: Re: [Mabadiliko] Paul Kagame: I asked America to kill Congo rebel leader with drone

To: "mabadilikotanzania@googlegroups.com"

Date: Wednesday, May 22, 2013, 1:27 AM

Subject: Re: [Mabadiliko] Paul Kagame: I asked America to kill Congo rebel leader with drone

To: "mabadilikotanzania@googlegroups.com"

Date: Wednesday, May 22, 2013, 1:27 AM

I Liked this one most; "We don't live our lives or we don't deal with our affairs more from the dictates from outside than from the dictates of our own situation and conditions," Kagame said. "The outside viewpoint, sometimes you don't know what it is. It keeps changing. They tell you they want you to respect this or fight this and you are doing it and they say you're not doing it the right way. They keep shifting goalposts and interpreting things about us or what we are doing to suit the moment." LKK

On Wed, May 22, 2013 at 1:37 AM, Nyoni Magoha <john.magoha@gmail.com> wrote:

Saturday 18 May 2013 Chris MacGreal in Kigal

In an exclusive interview with Chris McGreal in Kigali, Rwanda's president denies backing an accused Congolese war criminal and says challenge to senior US official proves his innocence

In an exclusive interview with Chris McGreal in Kigali, Rwanda's president denies backing an accused Congolese war criminal and says challenge to senior US official proves his innocence

In an exclusive interview with Chris McGreal in Kigali, Rwanda's president denies backing an accused Congolese war criminal and says challenge to senior US official proves his innocence

Rwanda's president, Paul Kagame, has rejected accusations from Washington that he was supporting a rebel leader and accused war criminal in the Democratic Republic of the Congo by challenging a senior US official to send a drone to kill the wanted man.

In an interview with the Observer Magazine, Kagame said that on a visit to Washington in March he came under pressure from the US assistant secretary of state for Africa, Johnnie Carson, to arrest Bosco Ntaganda, leader of the M23 rebels, who was wanted by the international criminal court (ICC). The US administration was increasing pressure on Kagame following a UN report claiming to have uncovered evidence showing that the Rwandan military provided weapons and other support to Ntaganda, whose forces briefly seized control of the region's main city, Goma.

"I told him: 'Assistant secretary of state, you support [the UN peacekeeping force] in the Congo. Such a big force, so much money. Have you failed to use that force to arrest whoever you want to arrest in Congo? Now you are turning to me, you are turning to Rwanda?'" he said. "I said that, since you are used to sending drones and gunning people down, why don't you send a drone and get rid of him and stop this nonsense? And he just laughed. I told him: 'I'm serious'."

Kagame said that, after he returned to Rwanda, Carson kept up the pressure with a letter demanding that he act against Ntaganda. Days later, the M23 leader appeared at the US embassy in Rwanda's capital, Kigali, saying that he wanted to surrender to the ICC. He was transferred to The Hague. The Rwandan leadership denies any prior knowledge of Ntaganda's decision to hand himself over. It suggests he was facing a rebellion within M23 and feared for his safety.

But Kagame's confrontation with Carson reflects how much relationships with even close allies have deteriorated over allegations that Rwanda continues to play a part in the bloodletting in Congo. The US and Britain, Rwanda's largest bilateral aid donors, withheld financial assistance, as did the EU, prompting accusations of betrayal by Rwandan officials. The political impact added impetus to a government campaign to condition the population to become more self-reliant.

Kagame is angered by the moves and criticisms of his human rights record in Rwanda, including allegations that he blocks opponents by misusing laws banning hate speech to accuse them of promoting genocide and suppresses press criticism. The Rwandan president is also embittered that countries, led by the US and UK, that blocked intervention to stop the 1994 genocide, and France which sided with the Hutu extremist regime that led the killings, are now judging him on human rights.

"We don't live our lives or we don't deal with our affairs more from the dictates from outside than from the dictates of our own situation and conditions," Kagame said. "The outside viewpoint, sometimes you don't know what it is. It keeps changing. They tell you they want you to respect this or fight this and you are doing it and they say you're not doing it the right way. They keep shifting goalposts and interpreting things about us or what we are doing to suit the moment."

He is agitated about what he sees as Rwanda being held responsible for all the ills of Congo, when Kigali's military intervention began in 1996 to clear out Hutu extremists using UN-funded refugee camps for raids to murder Tutsis. Kagame said that Rwanda was not responsible for the situation after decades of western colonisation and backing for the Mobutu dictatorship.

The Rwandan leader denies supporting M23 and said he has been falsely accused because Congo's president, Joseph Kabila, needs someone to blame because his army cannot fight. "To defeat these fellows doesn't take bravery because they don't go to fight. They just hear bullets and are on the loose running anywhere, looting, raping and doing anything. That's what happened," he said.

"President Kabila and the government had made statements about how this issue is going to be contained. They had to look for an explanation for how they were being defeated. They said we are not fighting [Ntaganda], we're actually fighting Rwanda."

More on This

Photo: Hugo Rami/IRIN

Photo: Hugo Rami/IRIN

Source: The Guardian (UK)

United States Department of State

(Washington, DC)

Congo-Brazzaville: Human Rights Reports: Republic of the Congo

19 April 2013

document

Photo: Hugo Rami/IRIN

Photo: Hugo Rami/IRIN

A traditional wooden boat floats on the Congo River of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Republic of the Congo is a parliamentary republic in which the constitution vests most of the decision-making authority and political power in the president and his administration. Denis Sassou-N'Guesso was reelected president in 2009 with 78 percent of the vote, but opposition candidates and domestic nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) questioned the validity of this figure. The 2009 election was peaceful, and the African Union declared the elections free and fair; however, opposition candidates and NGOs cited irregularities. Legislative elections were held in July and August 2011 for 137 of the National Assembly's 139 seats; elections could not be held in two electoral districts in Brazzaville because of the March 4 munitions depot explosions in the capital's Mpila neighborhood. The African Union declared the elections free, fair, and credible, while still citing numerous irregularities.

Civil society election observers estimated the participation rate for the legislative elections at 10 to15 percent nationwide. While the country has a multiparty political system, members of the president's Congolese Labor Party (PCT) and its allies won 95 percent of the legislative seats and occupied most senior government positions.

Security forces reported to civilian authorities. The government generally maintained effective control over the security forces; however, there some members of the security forces acted independently of government authority, committed abuses, and engaged in malfeasance.

Major human rights problems included beatings and torture of detainees by security forces, poor prison conditions, and lengthy pretrial detention.

Other human rights abuses included arbitrary arrest; an ineffective and underresourced judiciary; political prisoners; infringement of citizens' privacy rights; some restrictions on freedom of speech, press, and assembly; official corruption and lack of transparency; lack of adequate shelter for victims of the March 4 explosions; domestic violence, including rape; trafficking in persons; discrimination on the basis of ethnicity, particularly against indigenous persons; female genital mutilation/cutting; and child labor.

The government seldom took steps to prosecute or punish officials who committed abuses, whether in the security services or elsewhere in the government, and official impunity was a problem.

Section 1. Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom from:

a. Arbitrary or Unlawful Deprivation of Life

Is Kagame Africa's Lincoln or a tyrant exploiting Rwanda's tragic history?

In the second part of his special report, Chris McGreal meets President Paul Kagame in Kigali – and finds him angry

The warrior: Paul Kagame with RPF troops in 1993, during the civil war that preceded the genocide. Photograph: Joel Stettenheim/Corbis

The warrior: Paul Kagame with RPF troops in 1993, during the civil war that preceded the genocide. Photograph: Joel Stettenheim/Corbis

On the run: in 1996, Kagame’s troops drove Hutu refugees out of UN camps in Congo, and back to Rwanda. Photograph: Yunghi Kim/Contact Press Images

On the run: in 1996, Kagame’s troops drove Hutu refugees out of UN camps in Congo, and back to Rwanda. Photograph: Yunghi Kim/Contact Press Images

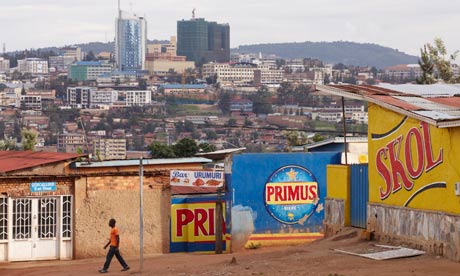

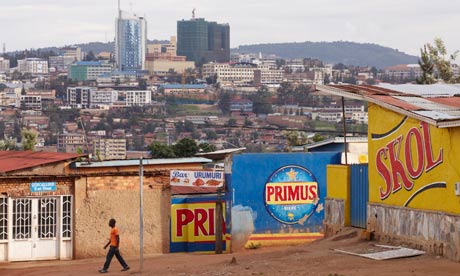

Facing the future: the changing skyline of the capital city, Kigali, now experiencing a period of economic growth. Photograph: Andy Hall for the Observer

Facing the future: the changing skyline of the capital city, Kigali, now experiencing a period of economic growth. Photograph: Andy Hall for the Observer

- The Observer, Saturday 18 May 2013

- Jump to comments (30)

Pressing the flesh: with Bill Clinton, who described Kagame as ‘one of the greatest leaders of our time’. Photograph: Ed Ou/Getty Images

Paul Kagame is angrier than I've ever seen him. Rwanda's president is famously direct with his critics. His contempt for governments he's crossed swords with, led by the French, is only marginally less vitriolic than his view of human-rights groups daring to lecture him, the rebel leader whose army put a stop to the 1994 genocide of 800,0000 Tutsis. But now even friends are regarded with suspicion to the point of hostility. Take London and Washington accusing Rwanda of perpetuating the interminable and bloody conflict across the border in Congo and flagging up concerns that Kagame is constructing a de-facto one-party state.

They are hypocrites, blind to their own histories, says Rwanda's president. "Who are these gods who police others for their rights?" he says in an interview with the Observer at the presidential office in Kigali. "One of the things I live for is to challenge that. I grew up in a refugee camp. Thirty years. This so-called human-rights world didn't ask me what was happening for me to be there 30 years."

Nearly two decades after the leader of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) emerged from the hills to overthrow the extremist Hutu regime trying to exterminate the Tutsi population, Kagame is still a combative and divisive figure. To some he is the Lincoln of Africa for rising above his country's old divisions – and his own suffering after narrowly escaping as a child across the border to Uganda during an earlier bout of Tutsi killing – to preach forgiveness, reconciliation and hard work as he forges a new Rwanda out of the ashes of genocide.

The warrior: Paul Kagame with RPF troops in 1993, during the civil war that preceded the genocide. Photograph: Joel Stettenheim/Corbis

The warrior: Paul Kagame with RPF troops in 1993, during the civil war that preceded the genocide. Photograph: Joel Stettenheim/Corbis

To others, Kagame has exploited his country's tragic history, and the west's guilt over its inaction during the slaughter, to construct a new Tutsi-dominated authoritarian regime using the legacy of genocide to suppress opposition and cover up for the crimes of his own side. In doing so, critics warn, he is laying the groundwork for another bout of bloodletting down the road.

For years, the heroic view of Kagame prevailed, not least in Britain and the US which, between them, provided about half the money to fund the Rwandan government's budget. But, in recent months, there's been a very public shift. Once-unquestioning support from Washington, where Bill Clinton called Kagame "one of the greatest leaders of our time", has given way to cuts in military aid and warnings from the US war crimes chief that Rwanda's leadership could find itself under investigation from the international criminal court over its backing for rebels in eastern Congo.

Britain, too, has stepped back from support so unequivocal that Clare Short, then Labour's international development secretary, called Kagame "a sweetie" and Tony Blair established a foundation to help the man he calls a "visionary leader" to govern. Britain's Conservative party has been no less enthusiastic. It set up a social-action project in Rwanda to bring hundreds of volunteers over recent years, including Tory MPs, to assist with construction of schools and community centres. Now the relationship is cooler as Congo's own tragedy, and Rwanda's part in it, can no longer be ignored.

A trail of imprisoned opponents, exiled former allies and assassinations pinned on Kagame by critics has also eaten away at his claims to be an enlightened, modernising leader who embraces new technology and is an enthusiastic blogger and tweeter. Among those locked up was Kagame's predecessor as president, Pasteur Bizimungu, while former allies from the RPF's days as a rebel army have fled abroad. They include Kagame's former chief aide, Theogene Rudasingwa, who formed a new political party with other exiles including former army chief of staff, General Faustin Kayumba Nyamwasa, who was wounded in an apparent assassination attempt in South Africa.

Another former ally, ex-interior minister Seth Sendashonga, who posed a serious political challenge after breaking with Kagame, was assassinated in Kenya 15 years ago. Rwanda's president has repeatedly denied any hand in the murder and several other apparently politically motivated killings since. But as a pattern of jailings, disappearances and deaths has developed there's no shortage of people ready to believe the worst.

Kagame increasingly takes a "with us or against us" view of even sympathetic criticism. The sharpness of his reaction suggests he was caught unawares by those he regarded as loyal friends deciding to keep a distance. He denies this. "Nothing would catch me off guard because I understand the world I live in. I understand it very well. And the world I live in is not necessarily a fair or just world. I have dealt with these injustices for the bigger part of my life," he says.

On the run: in 1996, Kagame’s troops drove Hutu refugees out of UN camps in Congo, and back to Rwanda. Photograph: Yunghi Kim/Contact Press Images

On the run: in 1996, Kagame’s troops drove Hutu refugees out of UN camps in Congo, and back to Rwanda. Photograph: Yunghi Kim/Contact Press Images

Part of what infuriates Kagame is what he sees as the age-old duplicity of neo-colonial powers. On the one hand politicians in western capitals are critical over democratic shortcomings in Rwanda. On the other, their diplomatic missions in Kigali praise Kagame for his single-minded, some say authoritarian, leadership in reconstructing his country and are wary of the day he leaves power.

Certainly, Rwanda is a better place than could have been imagined in the aftermath of the genocide. When Kagame's RPF rebels overthrew the Hutu extremist regime and seized power in 1994 they inherited a country dotted with mass graves and stripped of people. A sizeable proportion of the Hutu population fled across the borders to Zaire and Tanzania driven by fear, and a defeated Hutu leadership determined that Kagame should take over a "country without a people".

The Hutu army and its allied extremist militia, the interahamwe, were watered and fed in United Nations refugee camps even as they kept up the ethnic killings through cross-border raids. Kagame had few resources to draw on internally with many traditional institutions, such as the Catholic church, compromised by their part in the killings, including the involvement of priests and nuns in murder. Kagame's challenge was to reconstruct a country in which Tutsis could live without fear and the Hutu majority would accept him as its legitimate president.

A decade ago, one RPF regional military governor, Deo Nkusi, put it to me this way: "Changing people here is like bending steel. The people were bent into one shape over 40 years and they have to be bent back. If we do it too fast we will just break them. We have to exert pressure gradually."

Kagame was austere and demanding. He lambasted Rwandans as lazy and urged discipline. That appeared to reflect a view that the moral degeneracy underpinning the genocide was in part a product of a population insufficiently dedicated to hard work. The president urged Rwandans to confront the past and then put it behind them. Faced with 150,000 alleged killers packed into jails, his government spurned colonial-era courts in favour of a traditional form of justice that provided a forum for confessions and pleas for forgiveness by the killers, and laid the ground for a degree of reconciliation.

But Kagame takes nothing for granted. He says the path to a new Rwanda is through economic and social development that produces politics without hate. "The political, the economic, the social are tied together like the strands of a rope. The social and economic, if they are firm, tend to strengthen the other. In a state of poverty, illiteracy, people just remain exposed to all kinds of manipulation. That's what we have lived. It's easier to tell a poor person: you know what, you are poor, you're hungry because the other one has taken away your rights."

More than a million Rwandans have been lifted out of poverty since 2006. Access to healthcare and education is expanding. A construction boom has transformed the Kigali skyline. Kagame is also counting on time to solidify the gains. Two-thirds of Rwandans are under the age of 25 and open to a new way of thinking shaped by schools and learning the lessons of the past. But Kagame says he recognises that ridding Rwanda of the virus of hate and anger is not so simple.

"The reality of it is that things don't just disappear," he says. He points to the children that grew up without families. "It means they think about what created this situation where they have no families. So it's not just that they're growing up in a new situation and they have no bearing to the tragic past. Depending on how the situation continues to be managed, then the healing process – or the process of overcoming our past – becomes easier or more difficult." It is this achievement that has won Kagame previously unflinching support in many western capitals, even if it may be another generation before Rwandans can feel confident that, like Germany, they really have purged their past from their social fabric.

So it is all the more baffling and frustrating to Paul Kagame that he finds himself being called to account for a situation he says is not of Rwanda's making and is really the responsibility of the very people pointing the finger at him.

Rwanda's involvement in Congo has been undeniable since its 1996 invasion to clear the UN refugee camps used by Hutu extremists. The invasion evolved into a perpetual de-facto occupation in alliance with Congolese groups and the plunder of the region's considerable mineral resources by Rwanda, Burundi and Uganda. Security was an issue, but there was also money to be made.

Understanding for Rwanda's position eroded as eastern Congo fell under the control of warlords, and the people endured mass rape, massacres and starvation. Then, last year, a report by UN-appointed experts gave what it said was detailed evidence of the Rwandan military arming a mostly Tutsi rebel group in eastern Congo, M23, then led by a wanted war criminal, Bosco Ntaganda (who has since surrendered to the ICC).

Rwanda worked hard to discredit the report, but it triggered surprising reaction from those who had previously covered for Kagame. Washington said it found the UN research credible. The British also felt they could no longer turn a blind eye.

Facing the future: the changing skyline of the capital city, Kigali, now experiencing a period of economic growth. Photograph: Andy Hall for the Observer

Facing the future: the changing skyline of the capital city, Kigali, now experiencing a period of economic growth. Photograph: Andy Hall for the Observer

Kagame outright denies continuing Rwandan involvement in Congo and spends close to half an hour in a detailed explanation of why sending Rwandan troops there was a good thing, how the UN report was the stitching together of rumour, speculation and lies, and why it is decades of Belgian, French and American involvement in that blighted country that is the real cause of its problems. "I'm telling people look at themselves in the mirror. They are the ones responsible for problems in Congo, not me," he says.

"All the responsibilities that lie with the rest of the world, historically and in the present, have come to this: it is Rwanda responsible for all the problems. The Congolese themselves? No, not responsible for anything. Even the wasting of resources between Congo and the international community is something that has to be masked and packaged until Rwanda is made the problem.

"You have a [UN peacekeeping] mission in Congo spending $1.5bn every year for the past 12 years. Nobody ever asks: what do we get out of this? From the best arithmetic, I would say: why don't you give half of this to the Congolese to build schools, to build roads, to give them water and pay these soldiers who rape people every day? I'd even pay them not to rape."

Kagame goes on the attack over claims by the US and UK at diplomatic meetings to have additional evidence of Rwandan assistance to M23. "Up to this moment they've never given anybody a bit of what they're talking about – evidence," he says. The US froze military aid. Britain suspended some financial support and then put in place new controls. Kagame regards Rwanda as the victim of a diplomatic lynch mob and accuses the British government of laying the groundwork by sending the BBC and Channel 4 News to file reports critical of Rwanda. "It's just a circus. You start wondering about the people you're dealing with," he says.

The situation came to a head at a meeting between Kagame and ambassadors from the major foreign donors, including the UK and the US. I tell him I heard that diplomats had rarely seen him so furious. "Yes. Probably I was not angry enough. You can't have these people…" He trails off. "When you tell them the truth they think you are angry."

Part of what he says disturbs him is foreign governments cutting aid to the projects they have declared a success. What, he wonders, does that have to do with Congo? "How does affecting aid help deal with those things they are complaining about? It's simple logic. It doesn't make sense," he says.

But then he decides it does make sense because the aid freeze was not about Congo at all. "One thing that will never be said openly, but is a fact, aid is also a tool of control. It's not completely altruistic," he says. "If a country's giving us aid it doesn't give them the right to control us. I mean it. I can say thank you, you are really helpful. But you don't own me."

Kagame's anger rises again at what he says is western donors' insistence on talking about an issue he regards as having nothing to do with aid. "They say: these Rwandans think they are free, but actually they are not free. Sometimes it becomes a laughable matter, honestly." As with almost everything else in Rwanda, issues of freedom are bound up with the legacy of genocide. Kagame's critics say he is using laws intended to prevent the propagation of the kind of hate speech that contributed to the killings to suppress criticism of, and opposition to, the government. For some, the cause célèbre concerns Victoire Ingabire, leader of the Unified Democratic Forces, a coalition mostly of exiles, who attempted to challenge Kagame in the 2010 presidential election. She was arrested before the vote and subsequently sentenced to eight years in prison for inciting revolt, genocide ideology and forming an armed group.

Her supporters dismiss the charges as trumped up and hail her as a Rwandan version of Aung San Suu Kyi, the Burmese opposition leader. Foreign human rights groups have raised concerns about freedom of speech and the conduct of the trial after the principal witnesses against Ingabire were held incommunicado and possibly tortured into providing testimony.

But Ingabire's case also reflects the complexities of talking about the past in a country living with the legacy of genocide. On returning from 15 years' living in the Netherlands, Ingabire gave a speech at Kigali's genocide memorial, where thousands of victims are buried, equating the deaths of Hutus in the civil war with the murder of 800,000 Tutsis during the extermination campaign: "If we look at this memorial, it only refers to the people who died during the genocide against the Tutsis. There is another untold story with regard to the crimes against humanity committed against the Hutus. The Hutus who lost their loved ones are also suffering; they think about the loved ones who perished and are wondering, 'When will our dead ones also be remembered?'"

Tutsi survivors were outraged not only by the implication in her statements of a "double genocide", which they saw as intended to diminish the organised killings, but the choice of location at which to make the comments.

Ingabire's history casts doubt on her claim to have merely raised a legitimate issue for discussion. She is president of the Republican Rally for Democracy in Rwanda, a group born in the Hutu refugee camps in the mid-1990s with the backing of the politicians and army officers who carried out the genocide and who have spent the years since attempting to rewrite history.

Kagame points to the bans on Holocaust denial in France and Germany as evidence that foreign criticism over Ingabire's case is western hypocrisy. "The same people who have those laws (banning Holocaust denial) are saying we shouldn't have them. We're not blind to this," he says.

However, Ingabire's case does point up the limits on discussing what many Rwandans think are legitimate issues. Gonzaga Muganwa, a journalist and presenter of a radio phone-in, watched Ingabire's speech at the memorial. "We were so shocked. Nobody has heard such words spoken on Rwandan soil since the genocide," he says. "I myself wrote a piece saying Ingabire should be prosecuted. It's like saying Churchill bombing Dresden was the same as the Holocaust. The Tutsi genocide was an attempt to exterminate them." But Muganwa does have problems with restrictions on freedom of speech. He shakes his head over the case of two journalists jailed for genocide denial, divisionism and insulting Kagame. Rwanda's supreme court overturned the genocide-related convictions, but upheld those for defaming the president and public disorder. "Defaming the president should not be a criminal offence," says Muganwa.

He also confirms what other Rwandan journalists say: that they self-censor. Muganwa decided to look at the facts behind an issue widely if quietly discussed – a belief that a younger generation of Rwandans appointed to senior administrative positions in the government are mostly Tutsis who grew up in exile in neighbouring English-speaking Uganda, the same as many in the RPF leadership. It's a sensitive issue not only because it feeds into old Hutu extremist accusations of "Tutsi domination" but because of unhappiness at Tutsi exiles prospering while the genocide survivors still struggle in poverty.

"When I did my research I found that most of those people tended to speak English and some had family connections," says Muganwa. "I stopped because I know I would have been accused of creating divisions. I would have been open to prosecution. It's a no-go area. People discuss it in bars all the time, but you can't print it."

Muganwa goes on to raise the case of Frank Habineza and his Democratic Green Party of Rwanda. "I ask myself why the government refuses to register the Green party," he says.

As a former member of the RPF who broke with Kagame, no one could accuse Habineza of promoting genocide ideology. In 2010 he attempted to register the Greens for the presidential election, but fled the country after his party's vice president was found with his head cut off. Now he's back fighting what he believes is a deliberate government strategy to prevent him organising.

"It has not been easy. This government is lacking in recognition of political rights," he says. "You will not find anything divisive in what we've done, what we've said. The only thing we want is democracy, that people are consulted. We have a tendency here where the authorities just make a decision and hand it down to the people. Kagame is more interested in maintaining power and he will do anything to stay in power no matter what type of problems he leaves us with."

Kagame's response is to suggest that the concerns are all foreign inspired. "We really need to decide for ourselves, not what people on the outside decide for us," he says. "In terms of our internal political context, we manage it as our affairs. And the outsiders keep bringing in all kinds of poisons; we deal with that as well. But we have to deal with our lives as we deal with them, and keep managing those that come from outside as best we can to deal with it. And even tell them what they don't like to hear – that they bring prejudice and double standards in our own situation."

this raises the question of 2017. Rwanda's constitution requires Kagame to step down in four years, but already there are rumblings about changing it to allow him to stay on as president. Some of this is generated by the sycophancy expected of underlings wishing to remain in their leader's good graces, but there are other, unusual, forces at work as well.

A fair number of genocide survivors fear the day Kagame relinquishes power, believing his strong hand is all that keeps another bout of ethnic bloodletting at bay. There are also Hutus wary of political change because they see Rwanda's president as keeping a lid on violent Tutsi retaliation for the genocide. Others, including Kagame's own justice minister, believe it is essential for Kagame to step down in 2017 in order to maintain the primacy of the rule of law.

Kagame has been equivocal in the past, but greets the news of his justice minister's views with belligerence. "Why don't you tell him to step down himself? All those years he's been there, he's not the only one who can be the justice minister," he says. "In the end we should come to a view that serves us all. But in the first place I wonder why it becomes the subject of heated debate."

One of the reasons is that Rwandans are not alone in wondering if the final decision will really be the product of political consensus or, like so much else, ultimately decided by Kagame himself. Foreign governments have one eye on what they now regard as the salutary experience of dealing with Yoweri Museveni, president of neighbouring Uganda.

Two decades ago Museveni was hailed as one of a "new breed" of African leaders who broke with the plundering "presidents for life" and promised an era of good governance and freedoms. Museveni delivered to some extent, but there's no more talk of the new breed as Uganda's president heads toward his 30th year in power with little sign of political opponents being allowed to challenge him. When I tell Kagame there is a suspicion in some foreign capitals that he is treading in the footsteps of Museveni – a man regarded by some in the west as having betrayed his commitment to democracy – Rwanda's president returns to his favoured theme.

"Who are they, first of all, to feel betrayed? They are not gods. They don't create people. They don't own people. This whole thing of saying betrayed – betrayed by what?" he says.

Kagame wonders whether anybody ever accuses the Liberal Democratic party of Japan, which has ruled almost continuously since 1955, of clinging on to power. "I'm sure if the RPF went on for 40 years it would be a crime, but for the Liberal party in Japan it's not a crime. This is what disturbs me. Sometimes you feel like doing things just to challenge that – that somebody is entitled to do something, but says when you do it you are wrong. I find it bizarre," he says. "If it happens elsewhere and people think it's OK, why do people say it's not OK when it happens in Rwanda? I just don't accept this sort of thing. We have many struggles to keep fighting. Some of the things are like racism: 'These are Africans, we must herd them like cows.' No! Just refuse it."

This is misleading. "the rebel leader whose army put a stop to the 1994 genocide of 800,0000 Tutsis". How can Mc Greal forget/omit to mention that Kagame is the one who SPARKED the genocide by shooting down the plane that carried President Habyarimana, a Hutu? Kagame is even more responsible for that genocide because any sensible person could see that if an event like that was to happen, Tutsi were going to pay a big price because the 4 years war was between Hutu led by Habyarimana and Tutsi led by Kagame.

This tragedy has been a working capital for Kagame who has used it to justify his killing of 6 million congolese and committing a genocide on Hutu refugees in Congo as the UN MAPPING REPORT has documented it. It is a shame for McGreal to sound like already condemning Victoire Ingabire, while he at the same time puts her speech which is nothing than expressing a view on the Rwandan history that is different from Kagame's. Yes Kagame's thugs killed Hutus, they must be punished. Yes Hutus who killed Tutsis must also be punished. Let's not portray all Hutus as killers or all Tutsis as victims. We Rwandans know our history, stop re-writing it as you wish.Kagame is one of the criminals who should be at the ICC answering judges' questions. He never attempted promoting reconciliation because he is a bloody murderer who kills any body who tries to challenge him.

This tragedy has been a working capital for Kagame who has used it to justify his killing of 6 million congolese and committing a genocide on Hutu refugees in Congo as the UN MAPPING REPORT has documented it. It is a shame for McGreal to sound like already condemning Victoire Ingabire, while he at the same time puts her speech which is nothing than expressing a view on the Rwandan history that is different from Kagame's. Yes Kagame's thugs killed Hutus, they must be punished. Yes Hutus who killed Tutsis must also be punished. Let's not portray all Hutus as killers or all Tutsis as victims. We Rwandans know our history, stop re-writing it as you wish.Kagame is one of the criminals who should be at the ICC answering judges' questions. He never attempted promoting reconciliation because he is a bloody murderer who kills any body who tries to challenge him.

In an exclusive interview with Chris McGreal in Kigali, Rwanda's president denies backing an accused Congolese war criminal and says challenge to senior US official proves his innocence

Rwanda's president, Paul Kagame, has rejected accusations from Washington that he was supporting a rebel leader and accused war criminal in the Democratic Republic of the Congo by challenging a senior US official to send a drone to kill the wanted man.

In an interview with the Observer Magazine, Kagame said that on a visit to Washington in March he came under pressure from the US assistant secretary of state for Africa, Johnnie Carson, to arrest Bosco Ntaganda, leader of the M23 rebels, who was wanted by the international criminal court (ICC). The US administration was increasing pressure on Kagame following a UN report claiming to have uncovered evidence showing that the Rwandan military provided weapons and other support to Ntaganda, whose forces briefly seized control of the region's main city, Goma.

"I told him: 'Assistant secretary of state, you support [the UN peacekeeping force] in the Congo. Such a big force, so much money. Have you failed to use that force to arrest whoever you want to arrest in Congo? Now you are turning to me, you are turning to Rwanda?'" he said. "I said that, since you are used to sending drones and gunning people down, why don't you send a drone and get rid of him and stop this nonsense? And he just laughed. I told him: 'I'm serious'."

Kagame said that, after he returned to Rwanda, Carson kept up the pressure with a letter demanding that he act against Ntaganda. Days later, the M23 leader appeared at the US embassy in Rwanda's capital, Kigali, saying that he wanted to surrender to the ICC. He was transferred to The Hague. The Rwandan leadership denies any prior knowledge of Ntaganda's decision to hand himself over. It suggests he was facing a rebellion within M23 and feared for his safety.

But Kagame's confrontation with Carson reflects how much relationships with even close allies have deteriorated over allegations that Rwanda continues to play a part in the bloodletting in Congo. The US and Britain, Rwanda's largest bilateral aid donors, withheld financial assistance, as did the EU, prompting accusations of betrayal by Rwandan officials. The political impact added impetus to a government campaign to condition the population to become more self-reliant.

Kagame is angered by the moves and criticisms of his human rights record in Rwanda, including allegations that he blocks opponents by misusing laws banning hate speech to accuse them of promoting genocide and suppresses press criticism. The Rwandan president is also embittered that countries, led by the US and UK, that blocked intervention to stop the 1994 genocide, and France which sided with the Hutu extremist regime that led the killings, are now judging him on human rights.

"We don't live our lives or we don't deal with our affairs more from the dictates from outside than from the dictates of our own situation and conditions," Kagame said. "The outside viewpoint, sometimes you don't know what it is. It keeps changing. They tell you they want you to respect this or fight this and you are doing it and they say you're not doing it the right way. They keep shifting goalposts and interpreting things about us or what we are doing to suit the moment."

He is agitated about what he sees as Rwanda being held responsible for all the ills of Congo, when Kigali's military intervention began in 1996 to clear out Hutu extremists using UN-funded refugee camps for raids to murder Tutsis. Kagame said that Rwanda was not responsible for the situation after decades of western colonisation and backing for the Mobutu dictatorship.

The Rwandan leader denies supporting M23 and said he has been falsely accused because Congo's president, Joseph Kabila, needs someone to blame because his army cannot fight. "To defeat these fellows doesn't take bravery because they don't go to fight. They just hear bullets and are on the loose running anywhere, looting, raping and doing anything. That's what happened," he said.

"President Kabila and the government had made statements about how this issue is going to be contained. They had to look for an explanation for how they were being defeated. They said we are not fighting [Ntaganda], we're actually fighting Rwanda."

Source: The Guardian (UK)

Réf : 027/Prés-M23/2013

RE: Actual situation in the Eastern part of DRC

To the UN Secretary General

New York

Your Excellency,

We are once again honored to write to you about the situation that is taking place in the eastern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The military operations which are taking over in the surrounding of Goma are a result of Congolese army working together with his allies FDLR and MAI-MAI armed groups attacking the M23 positions from Monday 20th may, 2013 at 4:30 am.

We would like to see this military hostilities being stopped on both sides as it appears in our letter of 1st May, 2013 addressed to his Excellency MUSEVENI KAGUTA, President of the Republic of Uganda, Mediator of the Kampala peace talks and President of ICGLR, requesting for bilateral cease fire as shows our attached letter. Unfortunately the DRC government consider the Kampala negotiations as an opportunity for a delay, in order to obtain the UN resolution for a militarist option.

We again express our political will to have a bilateral cease fire agreement to bring peace to our people and allow the political dialogue to take over. We want this framework to deal with root causes of this conflict rather than a simple treatment of symptoms as it was recommended by H.E OLOUSSEGUN OBASANJO your Special Envoy in this very matter in the year 2008 – 2009.

We stay convinced that war will never bring sustainable peace in the DRC and want to assure you, that we believe that, the presence of the UN Mission in DRC remains an opportunity in our quest for peace .

Hoping that our correspondence will take your attention, we thank you anticipatively.

To the attention of Her Excellency Mary ROBINSON,

UN Secretary General Special Envoy in the Great Lakes Region

Re: Actual situation in the Eastern of DRC

Your Excellency,

We are once again honored to write to you about the situation that is taking place in the

eastern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The military operations which are taking over in the surrounding of Goma are a result of

Congolese army working together with his allies FDLR and MAI-MAI armed groups attacking the M23 positions from Monday 20th may, 2013 at 4:30 am.

This situation is disturbing the political peace process which was proned by the framework

agreement of Addis Ababa of February 24th 2013, the true way for solution in the DRC crisis

and even complicates the Kampala negotiations in which we did and do still build our hope.

We remain believing that war will never bring sustainable peace in the DRC.

We highly thank you, Excellency, as you endeavour to bring peace in our region through the

political solution rather than war.

Hoping that our correspondence will take your attention, we thank you anticipatively.

Re: Ceasefire Agreement

Your Excellency, Mr President,

We, at M23, are honored to inform you that we still have hope in peace through the negotiations taking place in Kampala.

Since December, 2012 on the request of the international community represented by the International Conference of Great Lakes Region, we submitted ourselves to all requests from the ICGLR, for instance we withdrew from Goma while we were militarily stronger than the DRC Army and we signed the unilateral ceasefire while the DRC government refused to do so. We maintained our military positions as it was requested and we humbly accepted all the demands which allowed the progress in the negotiations today, it’s during the Kampala negotiations period that the DRC government went to the UN seeking for the resolution 2098.

At this moment while we are still in negotiations, the DRC Army in coalition with the FDLR have left their positions, crossed over and took our positions in Mabenga. Others came from Tongo through the Virunga national Park where they are preparing to attack ours positions in Rutshuru territory.

In Kanyarutshina, the DRC Army in coalition with MONUSCO peace keepers took our positions, which consequently shows that the DRC government is preparing war against us. This is why we at M23, are requesting to the DRC government to sign the ceasefire agreement and to release all our members kept in prison in Kinshasa as a proof of willingness to pursue with negotiations.

We believe that the efforts made by the mediator and the ICGLR would not be taken in vain by the DRC government and we thank you for all.

| U.S. SEC requires company disclosures on use of DR Congo minerals |

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) on Wednesday approved a rule that would require public companies to disclose information on the use of minerals from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Under the rule, public companies would have to disclose annually their tracing of the minerals back to the sources if they use in their products the designated minerals from the DRC and neighboring countries, where armed groups have profited much from mining minerals used in electronics, jewelry and other goods... (view news)

|

M23 Political Leader Bertrand Bisimwa’s letter to Ban Ki Moon

Bunagana, May 22nd 2013

Réf : 027/Prés-M23/2013

RE: Actual situation in the Eastern part of DRC

To the UN Secretary General

New York

Your Excellency,

We are once again honored to write to you about the situation that is taking place in the eastern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The military operations which are taking over in the surrounding of Goma are a result of Congolese army working together with his allies FDLR and MAI-MAI armed groups attacking the M23 positions from Monday 20th may, 2013 at 4:30 am.

We would like to see this military hostilities being stopped on both sides as it appears in our letter of 1st May, 2013 addressed to his Excellency MUSEVENI KAGUTA, President of the Republic of Uganda, Mediator of the Kampala peace talks and President of ICGLR, requesting for bilateral cease fire as shows our attached letter. Unfortunately the DRC government consider the Kampala negotiations as an opportunity for a delay, in order to obtain the UN resolution for a militarist option.

We again express our political will to have a bilateral cease fire agreement to bring peace to our people and allow the political dialogue to take over. We want this framework to deal with root causes of this conflict rather than a simple treatment of symptoms as it was recommended by H.E OLOUSSEGUN OBASANJO your Special Envoy in this very matter in the year 2008 – 2009.

We stay convinced that war will never bring sustainable peace in the DRC and want to assure you, that we believe that, the presence of the UN Mission in DRC remains an opportunity in our quest for peace .

Hoping that our correspondence will take your attention, we thank you anticipatively.

Respectfully

Bertrand BISIMWA

CC:

- Permanent Members of the Security Council

- President of the African Union

- Heads of State of the CIRGL

- Embassies

- Permanent Members of the Security Council

- President of the African Union

- Heads of State of the CIRGL

- Embassies

M23 Leader Bertrand Bisimwa’s letter to Mary ROBINSON

Bunagana, May 22nd, 2013

Réf : 026/PRES-M23/2013

Réf : 026/PRES-M23/2013

To the attention of Her Excellency Mary ROBINSON,

UN Secretary General Special Envoy in the Great Lakes Region

Re: Actual situation in the Eastern of DRC

Your Excellency,

We are once again honored to write to you about the situation that is taking place in the

eastern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The military operations which are taking over in the surrounding of Goma are a result of

Congolese army working together with his allies FDLR and MAI-MAI armed groups attacking the M23 positions from Monday 20th may, 2013 at 4:30 am.

This situation is disturbing the political peace process which was proned by the framework

agreement of Addis Ababa of February 24th 2013, the true way for solution in the DRC crisis

and even complicates the Kampala negotiations in which we did and do still build our hope.

We would like to see this military hostilities being stopped on both sides as it appears in our

letter of 1st May, 2013 addressed to his Excellency MUSEVENI KAGUTA, President of the

Republic of Uganda, Mediator of the Kampala peace talks and President of ICGLR,

requesting for bilateral cease fire between us and the Government of the DRC.

letter of 1st May, 2013 addressed to his Excellency MUSEVENI KAGUTA, President of the

Republic of Uganda, Mediator of the Kampala peace talks and President of ICGLR,

requesting for bilateral cease fire between us and the Government of the DRC.

Unfortunately the DRC government consider the Kampala negotiations as an opportunity for a delay, in order to obtain the UN resolution for a militarist option.

We remain believing that war will never bring sustainable peace in the DRC.

We highly thank you, Excellency, as you endeavour to bring peace in our region through the

political solution rather than war.

Hoping that our correspondence will take your attention, we thank you anticipatively.

Respectfully

Bertrand BISIMWA

CC:

- UN Secretary General

- Permanent Members of the Security Council

- President of the African Union

- Heads of State of the CIRGL

- Embassies

- UN Secretary General

- Permanent Members of the Security Council

- President of the African Union

- Heads of State of the CIRGL

- Embassies

M23 letter To Yoweri Museveni Kaguta President of Uganda

Bunagana, May 1st, 2013

Réf : 021/Prés-M23/2013

Réf : 021/Prés-M23/2013

To His Excellency YOWERI MUSEVENI KAGUTA, President of Republic of Uganda,

Chairman of the International Conference of the Great Lakes Region “ICGLR” and Mediator of the negotiations between the DRC government and M23

Re: Ceasefire Agreement

Your Excellency, Mr President,

We, at M23, are honored to inform you that we still have hope in peace through the negotiations taking place in Kampala.

Since December, 2012 on the request of the international community represented by the International Conference of Great Lakes Region, we submitted ourselves to all requests from the ICGLR, for instance we withdrew from Goma while we were militarily stronger than the DRC Army and we signed the unilateral ceasefire while the DRC government refused to do so. We maintained our military positions as it was requested and we humbly accepted all the demands which allowed the progress in the negotiations today, it’s during the Kampala negotiations period that the DRC government went to the UN seeking for the resolution 2098.

At this moment while we are still in negotiations, the DRC Army in coalition with the FDLR have left their positions, crossed over and took our positions in Mabenga. Others came from Tongo through the Virunga national Park where they are preparing to attack ours positions in Rutshuru territory.

In Kanyarutshina, the DRC Army in coalition with MONUSCO peace keepers took our positions, which consequently shows that the DRC government is preparing war against us. This is why we at M23, are requesting to the DRC government to sign the ceasefire agreement and to release all our members kept in prison in Kinshasa as a proof of willingness to pursue with negotiations.

We are convinced that the ceasefire agreement will bring in the end of the war and allow peaceful negotiations to take place.

We believe that the efforts made by the mediator and the ICGLR would not be taken in vain by the DRC government and we thank you for all.

Respectfully

Bertrand BISIMWA

CC:

- Heads of States of ICGLR;

- His Excellence The Facilitator of Talks between M23 and The DRC’s Government;

- Heads of States of ICGLR;

- His Excellence The Facilitator of Talks between M23 and The DRC’s Government;

GOMA – RDC : Une tragédie à l’horizon

Qu’il s’agisse d’une escarmouche due à des raisons plus ou moins futiles -la gestion d’une source-, ou d’un accrochage plus sérieux qui pourrait mettre fin à cinq mois d’une trêve de facto, les combats qui ont opposée hier les soldats du M23 aux troupes gouvernementales et aux rebelles hutu rwandais des FDLR, leurs alliés, autour de l’abreuvoir de Mutaho -à une dizaine de kilomètres de Goma, dans l’Est de la RDC- préfigurent certainement une partie du scénario pour les semaines à venir.

Lorsque la Brigade d’intervention de la MONUSCO, mise en place par la résolution 2098 du Conseil de sécurité de l’ONU pour « neutraliser » les forces de l’Armée Révolutionnaire Congolaise, branche militaire du M23, sera prête à agir, il suffira un épisode déclencheur comme celui de Mutaho -une offensive conjointe FARDC-FDLR contre les positions de l’ARC et la riposte, quoique contenue, de cette dernière- pour susciter l’intervention sur le terrain de la nouvelle unité spéciale onusienne sous commandement d’un général tanzanien. Celle-ci ne se limitera pas, par conséquent, à exercer une fonction de dissuasion mais se déploiera en ordre de combat face aux troupes du général Sultani Makenga, chef militaire du M23.

Dans cette perspective d’« affrontement final » contre la « révolution congolaise » du M23, se consomme tristement la dérive des Nations Unies qui abdiquent leur rôle fondateur de partenariat mondial pour la paix pour se muer en force d’agression contre toute forme de résistance au nouvel ordre planétaire établi par les grandes puissances. Un ordre qui exige un pouvoir faible et prédateur en RDC avec Joseph Kabila à la tête de l’Etat et qui sera à tout prix défendu, même au risque d’embraser à nouveau la sous région. Ainsi, l’alliance qui se profile dans les collines et les jungles du Kivu entre Casques Blues, FARDC et FDLR signe -dans la collusion théoriquement contre nature entre une mission de paix devenue mission de guerre et des forces génocidaires- l’arrêt de mort de l’ONU en tant que régulateur impartial des conflits et la perte définitive de sa légitimation en tant qu’agent de paix.

Mais les événements de Mutaho nous apprennent une deuxième leçon. La provocation orchestrée par Kabila à la veille de la visite du Secrétaire général des NU à Kinshasa montre jusqu’à quel point le locataire du Palais de la Nation se sent conforté par ses parrains internationaux. Ceux-ci feront probablement mine de critiquer son inaction face aux engagements pris dans l’accord-cadre d’Addis-Abeba. Mais ils sont en réalité les derniers à être intéressés à un véritable processus de réformes en RDC, qui dote par exemple ce géant d’Afrique centrale d’une armée en mesure de faire respecter sa souveraineté nationale et d’un pouvoir capable d’en assurer le développement et de garantir le bien être de ses populations.

Pourtant, et avant qu’il ne soit pas trop tard, il faut au moins que les Etats de la sous région prennent la mesure des conséquences de l’intervention de la Brigade onusienne. Car tous ne resteront pas les bras croisés devant le nettoyage ethnique et l’extermination des communautés banyarwanda dans le Nord Kivu.

Luigi Elongui

Translated in English:

Whether it's a skirmish due to reasons more or less trivial-managing a source-or a more serious clash that could end in five months a de facto truce, fighting who opposed yesterday soldiers M23 government troops and Rwandan Hutu FDLR rebels, allies around the trough Mutaho to ten kilometers from Goma, in eastern DRC, certainly foreshadow some scenario for the coming weeks.When the Intervention Brigade of MONUSCO, established by resolution 2098 of the Security Council of the UN to "neutralize" the forces of the Congolese Revolutionary Army, the military wing of the M23 will be ready to act, simply a trigger episode like Mutaho-joint FARDC-FDLR offensive against the positions of the CRA and the response, although contained, this latest addition to spark action on the ground of the new UN special unit under the command of a Tanzanian general. This will not be limited, therefore, to exert a deterrent but will deploy in battle order against the troops of General Sultani Makenga military leader M23.In this perspective of "final battle" against the "Congolese revolution" of the M23, is sadly consumes drift UN abdicate their role founder of Global Partnership for Peace to turn into an aggressive force against any form of resistance the new world order established by the great powers. An order requiring low power and predator in the DRC with Joseph Kabila as head of state and will be defended at any cost, even at the risk of flare again the subregion. Thus, the alliance looming in the hills and jungles of Kivu between Helmets Blues, FARDC and FDLR sign-in collusion against theoretically kind between a peacekeeping mission to become war-forces genocidal death sentence UN as an impartial regulator of conflict and the final loss of its legitimacy as an agent of peace.But the events of Mutaho we learn a second lesson. Provocation orchestrated by Kabila on the eve of the visit of the UN Secretary General in Kinshasa shows how much the tenant of the Palace of the Nation feels buoyed by its international sponsors. They probably do mine to criticize his inaction on commitments made in the framework agreement in Addis Ababa. But in reality they are the last to be interested in a genuine process of reform in the DRC, which endows eg the giant Central African army in a position to enforce its national sovereignty and a power capable of ensure the development and ensure the welfare of its people.Yet, before it is too late, we need at least the countries of the sub region are measuring the impact of the intervention of the UN Brigade. Because all will not stand idly by ethnic cleansing and extermination of Banyarwanda in North Kivu communities.

RDC: Le viol est utilisé comme une arme de guerre

Par El Memey Murangwa

On aura tout vu dans ce pays qui par ses richesses fabuleuses devait devenir un paradis. Hélas ! Les guerres se succèdent emportant avec elles la joie des pauvres habitants qui ne savent à quels dieux confier leur désespoir. Impayés depuis belles lurettes, ceux qui sont commis à la protection des personnes et de leurs biens dévalisent, rançonnent, et sèment la mort. La femme paie le prix fort de cette escalade de violence.

Première nourricière de la famille depuis que l’emploi est devenu une denrée rare dans ce pays aux immenses terres arables, elle se réveille au grand matin, traverse la forêt dense pour aller au champ pour qu’au retour elle puisse bien nourrir sa maisonnée. Le plus souvent elle rentre en pleurs après avoir subi un traitement humiliant de la part des hommes en armes qui s’accaparent d’une grande partie de sa récolte et la viole à tour de rôle. Ces véreux n’hésitent même pas à faire de même sur la mineure d’âge qui accompagne sa maman.

De retour au village déserté par les hommes, elle est souvent accueillie par des lamentations provenant des vieilles mères qui maudissent les porteurs d’armes qui n’ont pas eu froid aux yeux en découvrant la nudité de ces personnes qui dans un passé récent avaient le respect de toutes les générations. Au Congo dit démocratique, l’état a cessé d’exister depuis une vingtaine d’années, dans les provinces des hommes en armes s’imposent et commettent l’arbitraire sur une population paupérisée par des dictatures successives.

Les intellectuels et les jeunes valides se réfugient dans les pays voisins en attendant de sauter sur la première possibilité de se rendre en occident pour une vie meilleure. Dans cette tragédie, le gouvernement reste silencieux. Au lieu de s’attaquer à ceux qui violent, les tenants du pouvoir autocratique ne s’intéressent qu’à ceux qui menacent le régime pendant que le viol continu de faire son chemin. Déshumanisé, les hommes abandonnent les femmes violés condamnant leurs progénitures à un avenir incertain. Les enfants nés de ces ignobles actes deviennent des enfants de la rue et constituent une pépinière qui très vite produit des violeurs impénitents. Au Congo le viol est devenue une arme de guerre, les victimes sont tenues en haleine par une armée d’inciviques qui étendent leurs autorités sur des espaces pouvant contribuer au développement de la nation congolaise.