World Bank Launches Initiative on Migration, Releases New Projections on Remittance Flows

April 19, 2013

WASHINGTON, April 19, 2013 – The World Bank today announced the establishment of the Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD), envisioned to become a global hub of knowledge and policy expertise on migration issues.

KNOMAD was initiated in response to the rapid growth in migration and remittances over the last decade. Nearly one billion people – that is, one out of every seven persons on the planet – have migrated internally and across international borders in search of better opportunities and living conditions, with profound implications for development.

Remittance flows to developing countries have more than quadrupled since 2000. Global remittances, including those to high-income countries, are estimated to have reached $514 billion in 2012, compared to $132 billion in 2000.

"Migration and remittances offer a vital lifeline for millions of people and can play a major role in an economy's take-off. They enable people to partake in the global labor market and create resources that can be leveraged for development and growth. But they are also a source of political contention, and for that very reason deserving of dispassionate analysis,” said Kaushik Basu, the World Bank’s Chief Economist and Senior Vice President for Development Economics, as he participated in an event to mark the launch of KNOMAD. “The World Bank has played a critical role in migration and remittance research and KNOMAD will be critical in taking this agenda forward."

Established with the support of Switzerland and Germany, KNOMAD aims to generate and synthesize knowledge on migration issues for countries; generate a menu of policy choices based on multidisciplinary knowledge and evidence; and provide technical assistance and capacity building to sending and receiving countries for the implementation of pilot projects, evaluation of migration policies, and data collection.

The program will focus on a number of key thematic areas: improving data on migration and remittance flows; skilled and low-skilled labor migration; integration issues in host communities; policy and institutional coherence; migration, security and development; migrant rights and social aspects of migration; demographic changes and migration; remittances, including access to finance and capital markets; mobilizing diaspora resources; environmental change and migration; and internal migration and urbanization. It will also address several cross-cutting themes, such as gender, monitoring and evaluation, capacity building, and public perceptions and communication.

Drawing on global expertise, KNOMAD’s outputs will be widely disseminated and will be available as global public goods.

According to the latest edition of the World Bank’s Migration and Development Brief, issued today, officially recorded remittance flows to developing countries grew by 5.3 percent to reach an estimated $401 billion in 2012. Remittances to developing countries are expected to grow by an annual average of 8.8 percent for the next three years and are forecast to reach $515 billion in 2015.

Given that many migrants send money and goods through people or informal channels, the true size of remittances are much larger than these official figures.

The top recipients of officially recorded remittances for 2012 are India ($69 billion), China ($60 billion), the Philippines ($24 billion), Mexico ($23 billion) and Nigeria and Egypt ($21 billion each). Other large recipients include Pakistan, Bangladesh, Vietnam, and Lebanon.

As a percentage of GDP, the top recipients of remittances, in 2011, were Tajikistan (47 percent), Liberia (31 percent), Kyrgyz Republic (29 percent), Lesotho (27 percent), Moldova (23 percent), Nepal (22 percent), and Samoa (21 percent).

“The role of remittances in helping lift people out of poverty has always been known, but there is also abundant evidence that migration and remittances are helping countries achieve progress towards other Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), such as access to education, safe water, sanitation and healthcare,” said Hans Timmer, Director of the Bank’s Development Prospects Group.

However, the high cost of sending money through official channels is an obstacle to the utilization of remittances for development purposes, as people seek out informal channels as their preferred means for sending money home. The global average cost for sending remittances was 9 percent in the first quarter of 2013, broadly unchanged from 2012.

The Brief also discusses efforts to feature migration and remittances in the Post-2015 Development Framework that is currently being discussed as we approach 2015, the target date for reaching the MDGs.

“Migration is a defining issue for global development,” said Dilip Ratha, Manager of the World Bank’s Migration and Remittances Unit and head of KNOMAD. “This underscores the need for an initiative such as KNOMAD, which will generate evidence-based research to facilitate constructive debate and discussion on migration issues with the aim of developing practical policy options for sending and receiving countries.”

Regional highlights:

The East Asia and Pacific region received an estimated $109 billion in remittances in 2012, about $5 billion lower than the estimate we made at the end of 2012, due mainly to a downward revision of inflows to China by the same amount. The first half of 2012 saw a substantial decline in remittances to China, which may be a reflection of fewer funds being channeled through officially recorded remittances into investments such as property, as the government seeks to dampen the overheated real estate market. Nevertheless, remittance inflows to the region were an increase of 2.5 percent over the 2011 value of $106 billion.

Remittances to Eastern Europe and Central Asia are estimated to have declined by 3.9 percent to about $40 billion in 2012, partly due to the depreciation of the euro against the US dollar (lowering remittances in dollar terms). Continued strong growth in oil-exporting Russia underpinned buoyant remittances to Tajikistan and Ukraine, while weak conditions in the Euro Area depressed remittances to Romania, Russia and Serbia. With officially recorded remittance inflows of about $6.5 billion in 2012, the Ukraine is the largest recipient in the region, followed by Russia ($5.7 billion), and Tajikistan ($3.7 billion). As economic conditions improve in Europe, and growth in Russia remains robust, officially recorded remittances to the region are expected to rebound in 2013-2015, exceeding the pre-crisis peak in 2014 and reaching US$52 billion in 2015.

The Latin America and Caribbean region saw a slight increase in remittances in 2012 to $62 billion, still more than $2.5 billion below the peak reached in 2008. Mexico, which received $23 billion in 2012, accounts for 56 percent of total remittances to the region, followed by Brazil ($4.9 billion). The US is the largest source of remittances to the region, accounting for 73 percent of the total inflows in 2012. Although the potential impact of immigration reform currently being considered in the US remains unclear, improvements in the US housing market and faster job creation this year are projected to underpin strong growth in officially recorded remittances to Latin America in 2013-2015, rising to over US$81 billion in 2015.

With remittance inflows of an estimated $49 billion in 2012 (an upward revision of about US$2 billion from previous estimates), the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region experienced the fastest expansion of remittances in 2012, growing by 14.3 percent over 2011. Egypt, which accounted for over 40 percent of total remittance inflows to the region, has seen a six-fold increase in remittances over the last eight years, making it the largest recipient in the region, ahead of Lebanon, Morocco, Jordan and Tunisia. Although Egypt has a large stock of highly skilled expatriates in the US, the UK and Europe, about two-thirds of its migrants are working in oil rich countries within the MENA region. Remittance flows to the MENA region are expected to grow by 5-6 percent, rising to $58 billion in 2015.

Officially recorded remittance flows to South Asia are estimated to have increased sharply by 12.8 percent to $109 billion in 2012. This follows growth averaging 13.8 percent in each of the previous two years. India remains the largest recipient country in the world, receiving $69 billion in 2012. In addition to large numbers of unskilled migrants working mainly in the oil-rich Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, India also has a large skilled diaspora the US and other high-income countries. Flows to Bangladesh, Pakistan and Nepal have also been robust, helped by strong economic growth in the GCC and India. Remittances to the region are projected to remain buoyant in the coming years, reaching $140 billion in 2015.

Remittance flows to Sub-Saharan Africa have been recovering from the contraction associated with the global financial crisis, but growth has been modest. In 2012, the region is estimated to have received about $31 billion in remittances, only about a 1 percent increase over 2011. Nigeria is by far the largest recipient of remittances in the region, accounting for about 67 percent of the inflows to the region in 2012, followed by Senegal and Kenya. Zero growth in flows to Nigeria in 2012 is partly attributable to the feeble labor market recovery of its major remittance source countries in Europe, the UK in particular. Remittance flows to Nigeria and the rest of the region are expected to grow significantly in the coming years to reach about $39 billion in 2015.

KNOMAD is now operational/New outlook for migration and remittances 2013-15 issued

The Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD) is shifting gears --- it has officially graduated from inception phase to being operational. An official launch event is being organized today, on the sidelines of the Spring Meetings of the World Bank and International monetary Fund (IMF). We’ve also held a meeting of the chairs and co-chairs of KNOMAD’s thematic working groups and will soon share with you the way forward.

We have also released today the latest issue of the Migration and Development Brief, which provides forecasts for remittance flows up to 2015 and updates data for 2012. The main highlights of the Brief are:

- Officially recorded remittance flows to developing countries reached an estimated $401 billion in 2012, growing by 5.3 percent compared with 2011. Remittance flows are expected to grow at an average of 8.8 percent annual rate during 2013-2015 to about $515 billion in 2015.

- Employment conditions in the US, including for migrants are improving, as also reflected in the quota for H-1B visas being rapidly filled for fiscal year 2014. Political momentum behind immigration reform in the US is growing.

- Average remittance prices were broadly unchanged at just above 9 percent over the last year, while the weighted average dropped in the first quarter of 2013 to an all-time low of 6.9 percent. While this suggests progress in reducing prices in high volume remittance corridors, prices continue to remain high in smaller corridors, affecting countries that have greater dependence on remittances.

- Migration and remittances are being featured in ongoing discussions on the Millennium Development Goals and the Post-2015 agenda.

Here’s the full Brief and a Press Release we issued today.

Migration is Development: Sutherland op-ed on migration and post-2015 development goals

In the run up to the UN High-Level Dialogue on Migration and Development that will take place in October 2013, there is a lot of discussion among migration experts on how migration might feature in the post-2015 development agenda. A foremost spokesperson for the migration community is Peter Sutherland, Chairman of Goldman Sachs International and the London School of Economics, and UN Special Representative for International Migration and Development (and former Director General of the World Trade Organization, EU Commissioner for Competition, and Attorney General of Ireland) has published a very timely, useful and well-written op-ed today, titled "Migration is Development". He writes,

"To succeed, the post-2015 agenda must break the original mold. It must be grounded in a fuller narrative about how development occurs – a narrative that accounts for complex issues such as migration. Otherwise, the global development agenda could lose its relevance, and thus its grip on stakeholders....[M]igration is the original strategy for people seeking to escape poverty, mitigate risk, and build a better life."

"There are an estimated 215 million international migrants today – a number expected to grow to 400 million by 2040 – and another 740 million internal migrants who have moved from rural to urban areas within countries. Each typically supports many family members back home, which also helps to lift entire communities."

"This is not to deny that migration has downsides. But migration is here to stay, and it is growing. There can be no return to a monoethnic past, so successful societies will need to adapt to diversity."

"Fortunately, the type of measurable outcomes that the MDGs have thus far demanded are being developed for migration."

"An ideal result would focus attention on the need to reduce the barriers to all kinds of human mobility – both internal and across national borders – by lowering its economic and social costs. Such an agenda includes simple measures, like reducing fees for visas, and more complex reforms, like allowing migrants to switch employers without penalty and increasing the proportion of migrants who enjoy legal protections and labor rights."

We at the Bank are closely involved with the GFMD (currently chaired by Sweden) and the Global Migration Group in trying to come up with development goals and indicators related to migration and post-2015 developement agenda. The KNOMAD is fully engaged in facilitating this process. This exercise will greatly help define the global agenda on migration and development in the coming decade, and hopefully change public perception of migrants in the North and the South.

How shall the World Bank succeed in this after failing and engaging in corruption with African leaders to ripoff Africa???

Eradicate Extreme Poverty and Hunger by 2015

- Q: How does food insecurity affect human and economic development?

- A: Children who are malnourished when they reach their second birthday could suffer permanent physical and cognitive damage, thereby affecting their future health, welfare, and economic well-being. For developing countries, the impact on their ability to raise a productive workforce can last for generations, while in the shorter term rising food prices can exacerbate inequality and lead to conflict and political instability.

World Bank: A First Responder to Global Crises

For more than 60 years, the World Bank has partnered with governments worldwide, reducing poverty by providing financial and technical help. But the recent food, fuel, and economic crises have dealt a triple blow to gains made toward achieving MDG 1. The World Bank has a track record of reacting quickly. Its development financing in FY09 saw an unprecedented 54% increase over FY08, helping to prevent malnutrition in young children and pregnant women; keep children in school and health clinics open; and expand nutrition programs and microfinance loans to women. Additionally, in 2008, the World Bank established the Global Food Crisis Response Program to assist the countries hardest hit by the dramatic rise in food prices. Peanuts are one of Mali’s primary exports.

Peanuts are one of Mali’s primary exports.- We can reduce poverty and hunger by:

- investing in agriculture

- creating jobs

- expanding social safety nets

- expanding nutrition programs that target children under two years of age

- universalizing education

- promoting gender equality

- protecting vulnerable countries during crises

Making Strides in Eradicating Poverty and Hunger

A meaningful path out of poverty requires a strong economy that produces jobs and good wages; a government that can provide schools, hospitals, roads, and energy; and healthy, well-nourished children who are the future human capital that will fuel economic growth. Economic growth in countries supported by IDA—the World Bank’s fund for the poorest countries—more than doubled from 2007 through 2009 compared with the previous 15 years. Real GDP per capita in those countries grew by 5.8% annually.Our Poverty and Hunger Strategy

- Provide governments zero-interest development financing, grants, and guarantees

- Offer technical assistance and other advisory services to reduce poverty and malnutrition

- Use safety nets and nutrition programs to cushion the impact of the food and financial crises

- The Bank has supported the provision of some 2.3 million school meals every day to children in low income countries.

- Increased support for agriculture and food security

- The World Bank Group is boosting spending on agriculture to some $6-8 billion a year from $4 billion in 2008.

- The Global Food Crisis Response Program (GFRP) is reaching some 40 million vulnerable people in 47 countries through $1.5 billion in support.

Some of Our MDG 1 Results

IDA is helping to achieve MDG 1 by providing $15 billion to the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative affecting 26 countries and $1.4 billion to social safety net programs in 39 countries.- Ethiopia: Increased number of people with access to safe water from 60% in 1990 to 94% in 2008.

- Senegal: Protected more than 500,000 people through dam rehabilitation.

- Armenia: Reduced electricity grid losses 22% between 2002 and 2007.

- India: A watershed management project in five districts resulted in a 66% increase in household income.

Global Monitoring Reports

Millennium Development Goals

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"MDG" redirects here. For other uses, see MDG (disambiguation).

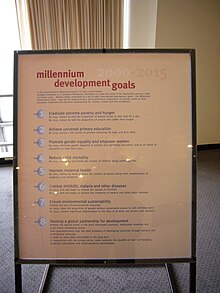

The Millennium Development Goals are a UN initiative.

- Eradicating extreme poverty and hunger,

- Achieving universal primary education,

- Promoting gender equality and empowering women,

- Reducing child mortality rates,

- Improving maternal health,

- Combating HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases,

- Ensuring environmental sustainability, and

- Developing a global partnership for development.[1]

Debate has surrounded adoption of the MDGs, focusing on lack of analysis and justification behind the chosen objectives, the difficulty or lack of measurements for some of the goals, and uneven progress towards reaching the goals, among other criticisms. Although developed countries' aid for achieving the MDGs has been rising over recent years, more than half the aid is towards debt relief owed by poor countries, with much of the remaining aid money going towards natural disaster relief and military aid which do not further development.

Progress towards reaching the goals has been uneven. Some countries have achieved many of the goals, while others are not on track to realize any. A UN conference in September 2010 reviewed progress to date and concluded with the adoption of a global action plan to achieve the eight anti-poverty goals by their 2015 target date. There were also new commitments on women's and children's health, and new initiatives in the worldwide battle against poverty, hunger, and disease.

Government organizations assist in achieving those goals, among them are the United Nations Millennium Campaign, the Millennium Promise Alliance, Inc., the Global Poverty Project, the Micah Challenge, The Youth in Action EU Programme, "Cartoons in Action" video project, and the 8 Visions of Hope global art project.

Background The aim of the MDGs is to encourage development by improving social and economic conditions in the world's poorest countries. They derive from earlier international development targets and were officially established following the Millennium Summit in 2000, where all world leaders in attendance adopted the United Nations Millennium Declaration The Millennium Summit was PEEd with the report of the Secretary-General entitled We the Peoples: The Role of the United Nations in the Twenty-First Century Additional input was prepared by the Millennium Forum, which brought together representatives of over 1,000 non-governmental and civil society organizations from more than 100 countries. The Forum met in May 2000 to conclude a two-year consultation process covering issues such as poverty eradication, environmental protection, human rights and protection of the vulnerable. The approval of the MDGs was possibly the main outcome of the Millennium Summit. In the area of peace and security, the adoption of the Brahimi Report was seen as properly equipping the organization to carry out the mandates given by the Security Council.[citation needed] The MDGs originated from the Millennium Declaration produced by the United Nations. The Declaration asserts that every individual has the right to dignity, freedom, equality, a basic standard of living that includes freedom from hunger and violence, and encourages tolerance and solidarity.The MDGs were made to operationalize these ideas by setting targets and indicators for poverty reduction in order to achieve the rights set forth in the Declaration on a set fifteen-year timeline.An Introduction to the Human Development and Capability Approach: Freedom and Agency' The Millennium Summit Declaration was, however, only part of the origins of the MDGs. It came about from not just the UN but also the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund. The setting came about through a series of UN‑led conferences in the 1990s focusing on issues such as children, nutrition, human rights, women and others. The OECD criticized major donors for reducing their levels of Official Development Assistance (ODA). With the onset of the UN's 50th anniversary, then UN Secretary General Kofi Annan saw the need to address the range of development issues. This led to his report titled, We the Peoples: The Role of the United Nations in the 21st Century which led to the Millennium Declaration. By this time, the OECD had already formed its International Development Goals (IDGs) and it was combined with the UN's efforts in the World Bank's 2001 meeting to form the MDGs."The Political Economy of the MDGs: Retrospect and Prospect for the World's Biggest Promise", The MDG focus on three major areas: of valorising human capital, improving infrastructure, and increasing social, economic and political rights, with the majority of the focus going towards increasing basic standards of living."The Millennium Development Goals Report:The objectives chosen within the human capital focus include improving nutrition, healthcare (including reducing levels of child mortality, HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria, and increasing reproductive health), and education. For the infrastructure focus, the objectives include improving infrastructure through increasing access to safe drinking water, energy and modern information/communication technology; amplifying farm outputs through sustainable practices; improving transportation infrastructure; and preserving the environment. Lastly, for the social, economic and political rights focus, the objectives include empowering women, reducing violence, increasing political voice, ensuring equal access to public services, and increasing security of property rights. The goals chosen were intended to increase an individual’s human capabilities and "advance the means to a productive life".The MDGs emphasize that individual policies needed to achieve these goals should be tailored to individual country’s needs; therefore most policy suggestions are general.

The MDGs also emphasize the role of developed countries in aiding developing countries, as outlined in Goal Eight. Goal Eight sets objectives and targets for developed countries to achieve a "global partnership for development" by supporting fair trade, debt relief for developing nations, increasing aid and access to affordable essential medicines, and encouraging technology transfer. Thus developing nations are not seen as left to achieve the MDGs on their own, but as a partner in the developing-developed compact to reduce world poverty.

[edit] Goals

A poster at the United Nations Headquarters in New York City, New York, USA, showing the Millennium Development Goals.

[edit] Goal 1: Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger

- Target 1A: Halve, between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people living on less than $1.25 a day [5]

- Proportion of population below $1.25 per day (PPP values)

- Poverty gap ratio [incidence x depth of poverty]

- Share of poorest quintile in national consumption

- Target 1B: Achieve Decent Employment for Women, Men, and Young People

- GDP Growth per Employed Person

- Employment Rate

- Proportion of employed population below $1.25 per day (PPP values)

- Proportion of family-based workers in employed population

- Target 1C: Halve, between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people who suffer from hunger

- Prevalence of underweight children under five years of age

- Proportion of population below minimum level of dietary energy consumption[6]

[edit] Goal 2: Achieve universal primary education

- Target 2A: By 2015, all children can complete a full course of primary schooling, girls and boys

- Enrollment in primary education

- Completion of primary education[7]

[edit] Goal 3: Promote gender equality and empower women

- Target 3A: Eliminate gender disparity in primary and secondary education preferably by 2005, and at all levels by 2015

- Ratios of girls to boys in primary, secondary and tertiary education

- Share of women in wage employment in the non-agricultural sector

- Proportion of seats held by women in national parliament[8]

- For girls in some regions, education remains elusive[9]

- Poverty is a major barrier to education, especially among older girls[9]

- In every developing region except the CIS, men outnumber women in paid employment[9]

- Women are largely relegated to more vulnerable forms of employment[9]

- Women are over-represented in informal employment, with its lack of benefits and security[9]

- Top-level jobs still go to men — to an overwhelming degree[9]

- Women are slowly rising to political power, but mainly when boosted by quotas and other special measures[9]

[edit] Goal 4: Reduce child mortality rates

- Target 4A: Reduce by two-thirds, between 1990 and 2015, the under-five mortality rate

- Under-five mortality rate

- Infant (under 1) mortality rate

- Proportion of 1-year-old children immunized against measles[10]

[edit] Goal 5: Improve maternal health

- Target 5A: Reduce by three quarters, between 1990 and 2015, the maternal mortality ratio

- Maternal mortality ratio

- Proportion of births attended by skilled health personnel

- Target 5B: Achieve, by 2015, universal access to reproductive health

- Contraceptive prevalence rate

- Adolescent birth rate

- Antenatal care coverage

- Unmet need for family planning[11]

[edit] Goal 6: Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases

- Target 6A: Have halted by 2015 and begun to reverse the spread of HIV/AIDS

- HIV prevalence among population aged 15–24 years

- Condom use at last high-risk sex

- Proportion of population aged 15–24 years with comprehensive correct knowledge of HIV/AIDS

- Target 6B: Achieve, by 2010, universal access to treatment for HIV/AIDS for all those who need it

- Proportion of population with advanced HIV infection with access to antiretroviral drugs

- Target 6C: Have halted by 2015 and begun to reverse the incidence of malaria and other major diseases

- Prevalence and death rates associated with malaria

- Proportion of children under 5 sleeping under insecticide-treated bednets

- Proportion of children under 5 with fever who are treated with appropriate anti-malarial drugs

- Incidence, prevalence and death rates associated with tuberculosis

- Proportion of tuberculosis cases detected and cured under DOTS (Directly Observed Treatment Short Course)[12]

[edit] Goal 7: Ensure environmental sustainability

- Target 7A: Integrate the principles of sustainable development into country policies and programs; reverse loss of environmental resources

- Target 7B: Reduce biodiversity loss, achieving, by 2010, a significant reduction in the rate of loss

- Proportion of land area covered by forest

- CO2 emissions, total, per capita and per $1 GDP (PPP)

- Consumption of ozone-depleting substances

- Proportion of fish stocks within safe biological limits

- Proportion of total water resources used

- Proportion of terrestrial and marine areas protected

- Proportion of species threatened with extinction

- Target 7C: Halve, by 2015, the proportion of the population without sustainable access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation (for more information see the entry on water supply)

- Proportion of population with sustainable access to an improved water source, urban and rural

- Proportion of urban population with access to improved sanitation

- Target 7D: By 2020, to have achieved a significant improvement in the lives of at least 100 million slum-dwellers

[edit] Goal 8: Develop a global partnership for development

- Target 8A: Develop further an open, rule-based, predictable, non-discriminatory trading and financial system

- Includes a commitment to good governance, development, and poverty reduction – both nationally and internationally

- Target 8B: Address the Special Needs of the Least Developed Countries (LDCs)

- Includes: tariff and quota free access for LDC exports; enhanced programme of debt relief for HIPC and cancellation of official bilateral debt; and more generous ODA (Official Development Assistance) for countries committed to poverty reduction

- Target 8C: Address the special needs of landlocked developing countries and small island developing States

- Through the Programme of Action for the Sustainable Development of Small Island Developing States and the outcome of the twenty-second special session of the General Assembly

- Target 8D: Deal comprehensively with the debt problems of developing countries through national and international measures in order to make debt sustainable in the long term

- Some of the indicators listed below are monitored separately for the least developed countries (LDCs), Africa, landlocked developing countries and small island developing States.

- Official development assistance (ODA):

- Net ODA, total and to LDCs, as percentage of OECD/DAC donors’ GNI

- Proportion of total sector-allocable ODA of OECD/DAC donors to basic social services (basic education, primary health care, nutrition, safe water and sanitation)

- Proportion of bilateral ODA of OECD/DAC donors that is untied

- ODA received in landlocked countries as proportion of their GNIs

- ODA received in small island developing States as proportion of their GNIs

- Market access:

- Proportion of total developed country imports (by value and excluding arms) from developing countries and from LDCs, admitted free of duty

- Average tariffs imposed by developed countries on agricultural products and textiles and clothing from developing countries

- Agricultural support estimate for OECD countries as percentage of their GDP

- Proportion of ODA provided to help build trade capacity

- Debt sustainability:

- Total number of countries that have reached their HIPC decision points and number that have reached their HIPC completion points (cumulative)

- Debt relief committed under HIPC initiative, US$

- Debt service as a percentage of exports of goods and services

- Target 8E: In co-operation with pharmaceutical companies, provide access to affordable, essential drugs in developing countries

- Proportion of population with access to affordable essential drugs on a sustainable basis

- Target 8F: In co-operation with the private sector, make available the benefits of new technologies, especially information and communications

- Telephone lines and cellular subscribers per 100 population

- Personal computers in use per 100 population

- Internet users per 100 Population[14]

[edit] Debate surrounding the MDGs

Drawbacks of the MDGs include the lack of analytical power and justification behind the chosen objectives.[15] The MDGs leave out important ideals, such as the lack of strong objectives and indicators for equality, which is considered by many scholars to be a major flaw of the MDGs due to the disparities of progress towards poverty reduction between groups within nations.[16][15] The MDGs also lack a focus on local participation and empowerment (excluding women’s empowerment) [Deneulin & Shahani 2009]. The MDGs also lack an emphasis on sustainability, making their future after 2015 questionable.[15] Thus, while the MDGs are a tool for tracking progress toward basic poverty reduction and provide a very basic policy road map to achieving these goals, they do not capture all elements needed to achieve the ideals set out in the Millennium Declaration.[16]Researchers also point out some important gaps in the MDGs. For example, agriculture was not specifically mentioned in the MDGs even though a major portion of world's poor are rural farmers. Again, MDG 2 focuses on primary education and emphasizes on enrollment and completion. In some countries, it has led to increase in primary education enrollment at the expense of learning achievement level. In some cases, it has also negatively affected secondary and post secondary education, which have important implication on economic growth.[17]

Another criticism of the MDGs is the difficulty or lack of measurements for some of the goals. Amir Attaran, an Associate Professor and Canada Research Chair in Law, Population Health, and Global Development Policy at University of Ottawa, argues that goals related to maternal mortality, malaria, and tuberculosis are in practice impossible to measure and that current UN estimates do not have scientific validity or are missing.[18] Household surveys are often used by the UN organisations to estimate data for the health MDGs.[18] These surveys have been argued to be poor measurements of the data they are trying to collect, and many different organisations have redundant surveys, which waste limited resources.[18] Furthermore, countries with the highest levels of maternal mortality, malaria, and tuberculosis often have the least amount of reliable data collection.[18] Attaran argues that without accurate measures of past and current data for the health related MDGs, it is impossible to determine if progress has been made toward the goals, leaving the MDGs as little more than a rhetorical call to arms.[18]

Proponents for the MDGs argue that while some goals are difficult to measure, that there is still validity in setting goals as they provide a political and operational framework to achieving the goals.[19] They also assert that non-health related MDGs are often well measured, and it is wrong to assume that all MDGs are doomed to fail due to lack of data.[19] It is further argued that for difficult to measure goals, best practices have be identified and their implication is measurable as well as their positive effects on progress. With an increase in the quantity and quality of healthcare systems in developing countries, more data will be collected, as well as more progress made.[19] Lastly the MDGs bring attention to measurements of well being beyond income, and this attention alone helps bring funding to achieving these goals.[15]

The MDGs are also argued to help the human development by providing a measurement of human development that is not based solely on income, prioritizing interventions, establishing obtainable objectives with operationalized measurements of progress (though the data needed to measure progress is difficult to obtain), and increasing the developed world’s involvement in worldwide poverty reduction.[15][20] The measurement of human development in the MDGs goes beyond income, and even just basic health and education, to include gender and reproductive rights, environmental sustainability, and spread of technology.[15] Prioritizing interventions helps developing countries with limited resources make decisions about where to allocate their resources through which public policies.[15] The MDGs also strengthen the commitment of developed countries to helping developing countries, and encourage the flow of aid and information sharing.[15] The joint responsibility of developing and developed nations for achieving the MDGs increases the likelihood of their success, which is reinforced by their 189-country support (the MDGs are the most broadly supported poverty reduction targets ever set by the world).[21]

[edit] Progress

Progress towards reaching the goals has been uneven. Some countries, such as Brazil, have achieved many of the goals,[22] while others, such as Benin, are not on track to realize any.[23] The major countries that have been achieving their goals include China (whose poverty population has reduced from 452 million to 278 million) and India due to clear internal and external factors of population and economic development.[24] The World Bank estimated that MDG 1A (halving the proportion of people living on less than $1 a day) was achieved in 2008 mainly due to the results from these two countries and East Asia.[25]However, areas needing the most reduction, such as the sub-Saharan Africa regions have yet to make any drastic changes in improving their quality of life. During the same time frame as China, sub-Saharan Africa reduced its poverty by a mere one percent and is at a major risk of not meeting the MDGs by 2015.[24] Even though the poverty rates in sub-Saharan Africa decreased in a small percent, there are some successes regarding millennium development goals in sub-Saharan Africa. In the case of MDG 1, sub-Saharan region started to eradicate poverty by strengthening the industry of rice production. Originally, rice production was one of the main problems since its production rate could not catch up the rapid population growth by mid‑1990s. This caused great amount of rice imports and great costs for the governments reaching nearly $1 billion annually. In addition, farmers in Africa suffered from finding the suitable species of rice that can well-adapt in their conditions with high-yield characteristic. Then, New Rice for Africa (NERCA) which is high-yielding and well adapting to the African conditions was developed and contributed to the food security in sub-Saharan regions including Congo Brazzaville, Côte d'Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Guinea, Kenya, Mali, Nigeria, Togo, and Uganda. Now about 18 varieties of the hybrid species are available to rice farmers and, for the first time, many farmers are able to produce enough rice to feed their families and to gain profit at the market.[26] Sub-Saharan region also show improvement in the case of MDG 2. School fees that included Parent-Teacher Association and community contributions, textbook fees, compulsory uniforms and other charges were highly expensive in sub-Saharan Africa, taking up nearly a quarter of a poor family’s income. This was one of the barriers for enrollment and, thus, countries like Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania, and Uganda have eliminated school fees. This resulted in the increase in student enrollment in several regions. For instance, in Ghana, public school enrollment in the most deprived districts soared from 4.2 million to 5.4 million between 2004 and 2005. In Kenya, enrollment of primary school children surged significantly with 1.2 million extra increase of children in school in 2003 and by 2004, the number had climbed to 7.2 million.[27] Fundamental issues will determine whether or not the MDGs are achieved, namely gender, the divide between the humanitarian and development agendas and economic growth, according to researchers at the Overseas Development Institute (ODI).[28][29][30]

Achieving the MDGs does not depend on economic growth alone and expensive solutions. In the case of MDG 4, some developing countries like Bangladesh have shown that it is possible to reduce child mortality with only modest growth with inexpensive but effective interventions, such as measles immunisation.[31] It has also been found that total government expenditure would not, in most cases, be enough to meet the agreed spending targets in a number of sectors highlighted by the MDGs.[32] Research on health systems and MDGs suggests that a "one size fits all" model will not sufficiently respond to the individual healthcare profiles of developing countries; however, the study does find a set of similar constraints in scaling up international health, including the lack of absorptive capacity, weak health systems, human resource limitations, and high costs. The study argues that the emphasis on quantitative coverage obscures the measures required for scaling up health care. These measures include political, organizational, and functional dimensions of scaling up, and the need to nurture local organizations.[33]

According to some experts, MDG 7—to halve the proportion of the population without sustainable access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation—is still far from being reached. Since national governments often cannot provide the necessary infrastructure, civil society in some countries started to organise and work on sanitation themselves, says the magazine D+C Development and Cooperation.[34] For instance, in Ghana there is an umbrella organisation called CONIWAS (Coalition of NGOs in Water and Sanitation), which today has more than 70 member organisations focusing on providing access to water and sanitation.

Goal 8 of the MDGs is unique in the sense that it focuses on donor government commitments and achievements, rather than successes in the developing world. The Commitment to Development Index, published annually by the Center for Global Development in Washington, D.C., is considered the best numerical indicator for MDG 8.[35] It is a more comprehensive measure of donor progress than official development assistance, as it takes into account policies on a number of indicators that affect developing countries such as trade, migration, and investment.

To accelerate progress towards the MDGs, the G‑8 Finance Ministers met in London in June 2005 (in preparation for the G‑8 Gleneagles Summit in July) and reached an agreement to provide enough funds to the World Bank, the IMF, and the African Development Bank (AfDB) to cancel an additional $40 to $55 billion in debt owed by members of the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC). This would allow impoverished countries to re-channel the resources saved from the forgiven debt to social programs for improving health and education.[36]

Backed by G-8 funding, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the AfDB each endorsed the Gleaneagles plan and implemented the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI) to effectuate the debt cancellations. The MDRI supplements HIPC by providing each country that reaches the HIPC completion point 100% forgiveness of its multilateral debt. Countries that previously reached the decision point became eligible for full debt forgiveness once their lending agency confirmed that the countries had continued to maintain the reforms implemented during HIPC status. Other countries that subsequently reach the completion point automatically receive full forgiveness of their multilateral debt under MDRI.[36]

While the World Bank and AfDB limit MDRI to countries that complete the HIPC program, the IMF's MDRI eligibility criteria are slightly less restrictive so as to comply with the IMF's unique "uniform treatment" requirement. Instead of limiting eligibility to HIPC countries, any country with annual per capita income of $380 or less qualifies for MDRI debt cancellation. The IMF adopted the $380 threshold because it closely approximates the countries eligible for HIPC.[37]

The International Health Partnership (IHP+) also aims to accelerate progress towards the MDGs by putting international principles for effective aid and development cooperation into practice in the health sector. In developing countries, money for health comes from both domestic and external sources, and governments must work in coordination with a range of international development partners. As these partners increase in number, variations in funding streams and bureaucratic demands also increase. As a result, development efforts can become fragmented and resources can be wasted. By encouraging support for a single national health strategy or plan, a single monitoring and evaluation framework, and a strong emphasis on mutual accountability, IHP+ builds confidence between government, civil society, development partners, and other stakeholders whose activities affect health.[38]

As 2015 approaches, however, increasing global uncertainties such as the economic crisis and climate change have led to an opportunity to rethink the MDG approach to development policy. According to the In Focus policy brief from the Institute of Development Studies, the "After 2015" debate is about questioning the value of an MDG-type, target-based approach to international development, about progress so far on poverty reduction, about looking to an uncertain future and exploring what kind of system is needed after the MDG deadline has passed.[39][40]

Further developments in rethinking strategies and approaches to achieving the MDGs include research by the Overseas Development Institute into the role of equity.[41] Researchers at the ODI argue progress can be accelerated due to recent breakthroughs in the role equity plays in creating a virtuous circle where rising equity ensures the poor participate in their country's develop and creates reductions in poverty and financial stability.[41] Yet equity should not be understood purely as economic, but also as political. Examples abound, including Brazil's cash transfers, Uganda's eliminations of user fees and the subsequent huge increase in visits from the very poorest or else Mauritius's dual-track approach to liberalisation (inclusive growth and inclusive development) aiding it on its road into the World Trade Organization.[41] Researchers at the ODI thus propose equity be measured in league tables in order to provide a clearer insight into how MDGs can be achieved more quickly; the ODI is working with partners to put forward league tables at the 2010 MDG review meeting.[41]

The effects of increasing drug use have been noted by the International Journal of Drug Policy as a deterrent to the goal of the MDGs.[42]

Other development scholars, such as Naila Kabeer, Caren Grown, and Noeleen Heyzer, argue that an increased focus on women’s empowerment and gender mainstreaming of MDG-related policies will accelerate the progress of the MDGs. Kabeer argues that increasing women’s empowerment and access to paid work will help reduce child mortality.[43] To illustrate, in South Asian countries, which have high levels of gender discrimination, babies often suffer from low birth weight due to limited access to healthcare and malnutrition. Since low-birth weight babies have limited chances of survival, improving women’s health by increasing their bargaining power in the family through paid work, will reduce child mortality. Another way empowering women will help accelerate the MDGs is the inverse relationship between mother’s schooling and child mortality, as well as the positive correlation between increasing a mother’s agency over unearned income and health outcomes of her children, especially girls. Increasing a mother’s education and workforce participation increases these effects. Lastly empowering women by creating economic opportunities for women decreases women’s participation in the sex market which decreases the spread of AIDS, an MDG in itself (MDG 6A).[43]

Grown asserts that the resources, technology and knowledge exist to decrease poverty through improving gender equality, it is just the political will that is missing.[44] She argues that if donor countries and developing countries together focused on seven "priority areas": increasing girl’s completion of secondary school, guaranteeing sexual and reproductive health rights, improving infrastructure to ease women’s and girl’s time burdens, guaranteeing women’s property rights, reducing gender inequalities in employment, increasing seats held by women in government, and combating violence against women, great progress could be made towards the MDGs.[44]

Kabeer and Heyzer believe that the current MDGs targets do not place enough emphasis on tracking gender inequalities in poverty reduction and employment as there are only gender goals relating to health, education, and political representation.[43][45] To encourage women’s empowerment and progress towards the MDGs, increased emphasis should be placed on gender mainstreaming development policies and collecting data based on gender.

Review Summit 2010

A major conference was held at UN headquarters in New York on 20–22 September 2010 to review progress to date, with five years left to the 2015 deadline.

The conference concluded with the adoption of a global action plan to achieve the eight anti-poverty goals by their 2015 target date. There were also major new commitments on women's and children's health, and major new initiatives in the worldwide battle against poverty, hunger and disease.

[edit] Challenges

Although developed countries' aid for the achievement of the MDGs have been rising over recent years, it has shown that more than half is towards debt relief owed by poor countries. As well, remaining aid money goes towards disaster relief and military aid which does not further the country into development. According to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2006), the 50 least developed countries only receive about one third of all aid that flows from developed countries, raising the issue of aid not moving from rich to poor depending on their development needs but rather from rich to their closest allies.[42]Many development experts question the MDGs model of transferring billions of dollars directly from the wealthy nation governments to the often bureaucratic or corrupt governments in developing countries. This form of aid has led to extensive cynicism by the general public in the wealthy nations and hurts support for expanding aid.

[edit] Controversy over funding of 0.7% of GNI

Over the past 35 years, the members of the UN have repeatedly made a "commit[ment] 0.7% of rich-countries' gross national income (GNI) to Official Development Assistance".[46] The commitment was first made in 1970 by the UN General Assembly.The text of the commitment was:

Each economically advanced country will progressively increase its official development assistance to the developing countries and will exert its best efforts to reach a minimum net amount of 0.7 percent of its gross national product at market prices by the middle of the decade.[47]However, there has been disagreement from the United States as well as other nations over the Monterrey Consensus that urged "developed countries that have not done so to make concrete efforts towards the target of 0.7 per cent of gross national product (GNP) as ODA to developing countries".[48][49]

[edit] Support for the 0.7% target

The UN "believe[s] that donors should commit to reaching the long-standing target of 0.7 percent of GNI by 2015".[47] In 2005 the European Union reaffirmed its commitment to the 0.7% aid targets, noting that "four out of the five countries, which exceed the UN target for ODA of 0.7%, of GNI are member states of the European Union".[50]Many organizations are working to bring U.S. political attention to the Millennium Development Goals. In 2007, The Borgen Project worked with then Senator Barack Obama on the Global Poverty Act, a bill requiring the White House to develop a strategy for achieving the goals. As of 2009, the bill has not passed, but Obama has since been elected president.[51][52]

[edit] Challenges to the 0.7% target

Many Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) nations, including key members such as the United States, are not progressing towards their promise of giving 0.7% of their GNP towards poverty reduction by the target year of 2015. Some nations' contributions have been criticized as falling far short of 0.7%.[53]John Bolton argues that the United States never agreed in Monterrey to spending 0.7% of GDP on development assistance. Indeed, Washington has consistently opposed setting specific foreign-aid targets since the UN General Assembly first endorsed the 0.7% goal in 1970.[54]

The Australian government has committed to providing 0.5% of GNI in International Development Assistance by 2015-2016.[55]

[edit] Improvements

To meet the challenge of overcoming global health inequalities and make foreign aid more effective in attaining the Millennium Development Goals, more health services are suggested to be provided to the developing countries. Since the living condition of the developing countries are not organized well and getting worse, many health workers removed from the poor countries to other places which offer a better paid and good living environment.[56] Even though the health workers who are willing to stay, they are not trained well. As a result, these health care workers infected disease when they worked at the poor countries. Cuba, a small, low-income country, played a significant role of providing medical services to developing nations; it has trained more than 14,500 medical students from 30 different countries at its Latin American School of Medicine in Havana since 1999. Moreover, Cuba had 36000 health physicians worked in 72 countries, from Europe to Southeast Asia, 31 African countries, and 29 countries in the America. Countries such as Honduras, Guatemala, and Nicaragua depend on Cuban assistance to improve their living conditions.[57] It is noted that the training of health care workers should be counted as a budget consideration of developed countries.Furthermore, in order to achieve the MDGs, it is important to make services more accessible to people living in lower-income countries. Wealthy countries should cooperate with low- and middle-income countries by operating programs both in the short and long run. Besides that, some researchers suggested that developed countries should treat global health inequalities and humanitarian issue as a part of national strategy.

[edit] Post 2015 development agenda

At the September 2010 MDG Summit, UN Member States initiated steps towards advancing the Post-2015 Development Agenda and are now leading a process of open, inclusive consultations on the post-2015 agenda. Civil society organizations from all over the world have also begun to engage in the post-2015 process, while academia and other research institutions, including think tanks, are particularly active.[58]The United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction started a process of consultations as the disaster risk reduction community heads toward the end date of the current blueprint for global disaster risk reduction, the Hyogo Framework of Action 2005-2015: Building the Resilience of Nations and Communities to Disasters.[59]

On 31 July 2012, Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon appointed 26 civil society, private sector, and government leaders from all regions to a high-level panel to advise on the global development agenda beyond 2015.[60]

[edit] Related organizations

| This section requires expansion. (December 2009) |

The Millennium Promise Alliance, Inc. (or simply the "Millennium Promise") is a U.S.-based non-profit organization dedicated to achieving the Millennium Development Goals founded in 2005 by Special Advisor on the MDGs to the UN Secretary General Jeffrey Sachs and Wall Street leader and philanthropist, Ray Chambers.[61] Millennium Promise coordinates the Millennium Villages Project in partnership with Columbia's Earth Institute and the UNDP; it aims to demonstrate the feasibility of achieving the MDGs through an integrated, community-led approach to holistic development. The Millennium Villages Project currently operates in 14 sites across 10 countries in sub-Saharan Africa.[62]

The Global Poverty Project[63] is an international education and advocacy organisation using its multimedia presentation 1.4 Billion Reasons to educate people about the Millennium Development Goals and our capacity to end extreme poverty within a generation. They travel to workplaces, schools, universities, community groups and churches around Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States to equip people with the knowledge and resources they need to encourage the achievement of the MDGs.

The Micah Challenge is an international campaign that encourages Christians to support the Millennium Development Goals. Their aim is to "encourage our leaders to halve global poverty by 2015".[64]

The Youth in Action EU Programme "Cartoons in Action" project[65] created stop motion animation videos about MDGs,[66] a video channel "8 gol x 8 Millennium Development Goals"[67] and 21 Videos about 21 MDGs Targets using Arcade C64 videogames[66][68]

8 Visions of Hope is a global art project that explores and shows how art, culture, artists & musicians as positive change agents can help in the realization of the eight UN Millennium Development Goals.

The Development Education Unit of Future Worlds Center envisions, designs and implements development education awareness campaigns, trainings, conferences and resources since 2005. Leads a number of Europe-wide projects such as the Accessing Development Education and TeachMDGs.

[edit] Related projects

[edit] Accessing Development Education

Accessing Development Education[69] is a web portal developed by Future Worlds Center within an EU funded project (ONG-ED/2007/136-419). It provides relevant information about development and global education and helps educators share resources and materials that are most suitable for their work.[edit] TeachMDGs

The Teach MDGs European project led by Future Worlds Center aims to increase awareness and public support for the Millennium Development Goals by actively engaging teacher training institutes, teachers and pupils in developing local oriented teaching resources promoting the MDGs with a particular focus on sub-Saharan Africa and integrate these into the educational systems.[edit] UN Goals

UN Goals is a global project dedicated to spreading knowledge of these millennium goals through many different means through various internet and offline awareness campaigns.[edit] See also

- 8, a series of eight short films about the eight MDGs

- Debt relief

- Declaration of Human Duties and Responsibilities

- International development

- Official development assistance (ODA)

- Precaria (country)

- Seoul Development Consensus

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)

[edit] References

- ^ Background page,

- Halve by 2015 the proportion of people without sustainable access to safe drinking water United Nations Millennium Development Goals website, retrieved 16 June 2009.

- ^ "United Nations Millennium Development Goals". Un.org. 2008-05-20. Retrieved 2012-10-18.

- ^ "Tracking the Millennium Development Goals". Mdg Monitor. 2011-05-16. Retrieved 2012-10-18.

- ^ "List of goals, targets, and indicators". Siteresources.worldbank.org. Retrieved 2012-10-18.

- ^ http://content.undp.org/go/cms-service/stream/asset/;jsessionid=aMgXw9lbMbH4?asset_id=2620072. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ "Goal :: Eradicate Extreme Poverty and Hunger". Mdg Monitor. Retrieved 2012-10-18.

- ^ "Goal :: Achieve Universal Primary Education". Mdg Monitor. 2011-05-15. Retrieved 2012-10-18.

- ^ "Goal :: Promote Gender Equality and Empower Women". Mdg Monitor. 2011-04-30. Retrieved 2012-10-18.

- ^ a b c d e f g "United Nations Millennium Development Goals". Un.org. 2008-05-20. Retrieved 2012-10-18.

- ^ "Goal :: Reduce Child Mortality". Mdg Monitor. 2011-05-16. Retrieved 2012-10-18.

- ^ "Goal :: Improve Maternal Health". Mdg Monitor. Retrieved 2012-10-18.

- ^ "Goal :: Combat HIV/AIDS, Malaria and Other Diseases". Mdg Monitor. Retrieved 2012-10-18.

- ^ "Goal :: Ensure Environmental Sustainability". Mdg Monitor. Retrieved 2012-10-18.

- ^ "Goal :: Develop a Global Partnership for Development". Mdg Monitor. Retrieved 2012-10-18.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Séverine Deneulin with Lila Shahani (2009). "An Introduction to the Human Development and Capability Approach: Freedom and Agency". Sterling, VA: Earthscan. Retrieved November 15, 2010.

- ^ a b Can the MDGs provide a pathway to social justice?: The challenge of intersecting inequalities. 2010. Naila Kabeer for Institute of Development Studies.

- ^ Waage, Jeff, et al, (18 September 2010). "The Millennium Development Goals: a cross-sectoral analysis and principles for goal setting after 2015 url=http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(10)61196-8/fulltext". The Lancet 376 (9745): 991–1023.(registration required)

- ^ a b c d e Amir Attaran. 2005. An Immeasurable Crisis? A Criticism of the Millennium Development Goals and Why They Cannot Be Measured. 2005. PLoS Medicine | October 2005 | Volume 2 | Issue 10 | e318

- ^ a b c McArthur, J. W., Sachs, J. D., Schmidt-Traub, G. Response to Amir Attaran. 2005. PLoS Med 2(11): e379. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020379

- ^ Andy Haines and Andrew Cassels. 2004. "Can The Millennium Development Goals Be Attained?" BMJ: British Medical Journal, Vol. 329, No. 7462 (Aug. 14, 2004), pp. 394-397

- ^ United Nations. 2006. "The Millennium Development Goals Report: 2006." United Nations Development Programme, www.undp.org/publications/MDGReport2006.pdf (accessed January 2, 2008).

- ^ "Brazil: Quick Facts". MDG Monitor. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ^ "Benin: Quick Facts". MDG Monitor. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ^ a b "Halving Global Poverty" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ^ Chen, Shaohua and Martin Ravallion, (29 February 2012) "An Update to the World Bank’s Estimates of Consumption Poverty in the Developing World" Development Research Group, World Bank, Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ "Goal :: Tracking the Millennium Development Goals". Mdg Monitor. 2007-11-01. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ^ "Goal: Tracking the Millennium Development Goals". MDG Monitor. 1 November 2007. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ^ "Gender and the MDGs". ODI Briefing Paper. Overseas Development Institute. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- ^ "MDGs and the humanitarian-development divide". ODI Briefing Paper. Overseas Development Institute. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- ^ "Economic Growth and the MDGs". ODI Briefing Paper. Overseas Development Institute. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ The Feasibility of Financing Sectoral Development Targets

- ^ Subramanian, Savitha; Joseph Naimoli, Toru Matsubayashi, David Peters (2011). "Do We Have the Right Models for Scaling Up Health Services to Achieve the Millennium Development Goals?". BMC Health Services Research 11 (336). doi:10.1186/1472-6963-11-336.

- ^ "Yirenya-Tawiah/Tweneboah Lawson: Civil society is paving the way towards better sanitation in Ghana - Development and Cooperation - International Journal". Dandc.eu. Retrieved 2012-10-18.

- ^ Human Development Report 2003

- ^ a b E. Carrasco, C. McClellan, & J. Ro (2007) "Foreign Debt: Forgiveness antetretetred Repudiation" University of Iowa Center for International Finance and Development E-Book

- ^ E. Carrasco, C.McClellan, & J. Ro (2007), "Foreign Debt: Forgiveness antetretetred Repudiation" University of Iowa Center for International Finance and Development E-Book

- ^ "IHP+ The International Health Partnership". Internationalhealthpartnership.net. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ^ "After 2015 / Blogs - The Broker". Thebrokeronline.eu. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ^ "After 2015: Rethinking Pro-Poor Policy" Institute of Development Studies (IDS) In Focus Policy Brief 9.1. June 2009.

- ^ a b c d Vandemoortele, Milo (2010) "The MDGs and Equity", Overseas Development Institute.

- ^ a b Singer, M. 2008. "Drugs and Development: The Global Impact of Drug Use and Trafficking on Social and Economic Development. International Journal of Drug Policy 19 (6):467-478.

- ^ a b c Kabeer, Naila. 2003. Gender Mainstreaming in Poverty Eradication and the Millennium Development Goals: A Handbook for Policy-Makers and Other Stakeholders. Commonwealth Secretariat.

- ^ a b Grown, Caren. 2005. "Answering the Skeptics: Achieving Gender Equality and the Millennium Development Goals". Development 48(3): 82–86.

- ^ Noeleen Heyzer. 2005. "Making the Links: Women's Rights and Empowerment Are Key to Achieving the Millennium Development Goals". Gender and Development, Vol. 13, No. 1, Millennium Development Goals (March 2005), pp. 9-12

- ^ "Press Archive". UN Millennium Project. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ^ a b "Publications". UN Millennium Project. 2007-01-01. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ^ "United Nations Report of the International Conference on Financing for Development" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ "External Relations Council, Brussels 24 May 2005". Unmillenniumproject.org. Retrieved 2012-10-18.

- ^ Posted on (8 June 2007). "Borgen Back from Capitol Hill". Borgen Project News. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ^ Posted on (10 December 2006). "Highlight of Borgen’s 2006 Congressional Meetings". Borgen Project News. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ^ "Poverty Can Be Halved If Efforts Are Coupled with Better Governance, says TI". UN Millennium Project. Retrieved 2012-10-18.

- ^ "Bush Balks at Pact to Fight Poverty". BusinessWeek online. September 2, 2005.

- ^ [3][dead link]

- ^ Haines, Andy; Andrew Cassels (August 2004). "Can the Millennium Development Goals Be Attained?". British Medical Journal. 329(7462).

- ^ Huish, Robert (2009). "Canadian Foreign Aid for Global Health: Human Secruity Opportunity Lost". Can Foreign Policy (1192-6422): 60.

- ^ "United Nations Millennium Development Goals". Un.org. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ^ "Towards a post-2015 framework for Disaster Risk Reduction". Preventionweb.net. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ^ "UN Secretary-General Appoints High-Level Panel on Post-2015 Development Agenda". Un.org. Retrieved 2012-10-18.

- ^ "Overview". Millennium Promise. Retrieved 2012-10-18.

- ^ "Millennium Villages". Millennium Villages. Retrieved 2012-10-18.

- ^ "Welcome | Netherlands". Global Poverty Project. 2010-05-17. Retrieved 2012-10-18.

- ^ "Home". Micah Challenge. 2012-10-09. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ^ "Cartoons in action Progetto Gioventù in Azione finanziato dallANG - Agenzia Nazionale per i Giovani Youth in Action EU Programme. Il presente progetto è finanziato con il sostegno della Commissione europea. | Wix.com". Socialab.wix.com. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ^ a b R.I.P. giovane e dolce Melissa. "Cartoons inAction". YouTube. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ^ "8 gol x 8 Millennium Development Goals". YouTube. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ^ "MDGs". YouTube. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ^ "Welcome to the Development Education online Depository!". Developmenteducation.info. Retrieved 2012-10-18.

[edit] External links

- Official website

- Eradicate Extreme Poverty and Hunger by 2015 | UN Millennium Development Goal curated by the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies at Michigan State University

- Ensure Environmental Sustainability by 2015 | UN Millennium Development Goal curated by the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies at Michigan State University

- Gillian Sorensen, Senior Advisor to the United Nations Foundation, discusses UN Millennium Development Goals

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

No comments:

Post a Comment