When

the Clintons last occupied the White House, Sidney Blumenthal cast

himself in varied roles: speechwriter, in-house intellectual and press

corps whisperer. Republicans added another, accusing Mr. Blumenthal of

spreading gossip to discredit Republican investigators, and forced him

to testify during President Bill Clinton’s impeachment trial.

Now, as Hillary Rodham Clinton

embarks on her second presidential bid, Mr. Blumenthal’s service to the

Clintons is again under the spotlight. Representative Trey Gowdy of

South Carolina, a Republican who is leading the congressional committee

investigating the 2012 attacks in Benghazi, Libya, plans to subpoena Mr.

Blumenthal, 66, for a private transcribed interview.

Mr.

Gowdy’s chief interest, according to people briefed on the inquiry, is a

series of memos that Mr. Blumenthal — who was not an employee of the

State Department — wrote to Mrs. Clinton about events unfolding in Libya

before and after the death of Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi. According to

emails obtained by The New York Times, Mrs. Clinton, who was secretary

of state at the time, took Mr. Blumenthal’s advice seriously, forwarding

his memos to senior diplomatic officials in Libya and Washington and at

times asking them to respond. Mrs. Clinton continued to pass around his

memos even after other senior diplomats concluded that Mr. Blumenthal’s

assessments were often unreliable.

But

an examination by The Times suggests that Mr. Blumenthal’s involvement

was more wide-ranging and more complicated than previously known,

embodying the blurry lines between business, politics and philanthropy

that have enriched and vexed the Clintons and their inner circle for

years.

While

advising Mrs. Clinton on Libya, Mr. Blumenthal, who had been barred

from a State Department job by aides to President Obama, was also

employed by her family’s philanthropy, the Clinton Foundation, to help

with research, “message guidance” and the planning of commemorative

events, according to foundation officials. During the same period, he

also worked on and off as a paid consultant to Media Matters and

American Bridge, organizations that helped lay the groundwork for Mrs.

Clinton’s 2016 campaign.

Much

of the Libya intelligence that Mr. Blumenthal passed on to Mrs. Clinton

appears to have come from a group of business associates he was

advising as they sought to win contracts from the Libyan transitional

government. The venture, which was ultimately unsuccessful, involved

other Clinton friends, a private military contractor and one former

C.I.A. spy seeking to get in on the ground floor of the new Libyan

economy.

The

projects — creating floating hospitals to treat Libya’s war wounded and

temporary housing for displaced people, and building schools — would

have required State Department permits, but foundered before the

business partners could seek official approval.

It

is not clear whether Mrs. Clinton or the State Department knew of Mr.

Blumenthal’s interest in pursuing business in Libya; a State Department

spokesman declined to say. Many aspects of Mr. Blumenthal’s involvement

in the planned Libyan venture remain unclear. He declined repeated

requests to discuss it.

But

interviews with his associates and a review of previously unreported

correspondence suggest that — once again — it may be difficult to

determine where one of Mr. Blumenthal’s jobs ended and another began.

Mr.

Gowdy’s committee on the attacks in Benghazi hopes to ask Mr.

Blumenthal who, if anyone, was paying him to prepare the memos for Mrs.

Clinton and whether they were among his responsibilities at the Clinton

Foundation. The committee’s investigators are also interested in whether

the planned business venture in Libya posed any potential conflicts for

Mr. Blumenthal or Mrs. Clinton, whose aides the business partners

sought meetings with in early 2012.

The

Libya venture came together in 2011 when David L. Grange, a retired

Army major general, joined with a newly formed New York firm,

Constellations Group, to pursue business leads in Libya. Constellations

Group, led by a professional fund-raiser and philanthropist named Bill

White, was to provide the leads. Mr. Grange’s company, Osprey Global

Solutions, based in North Carolina, would put “boots on the ground to

see if there was an opportunity to do business,” Mr. Grange said in an

interview.

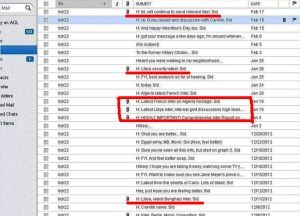

Inside the Documents

What Sidney Blumenthal’s memos to Hillary Clinton said,

and how they were handled: In 2011 and 2012, Mrs. Clinton received at

least 25 memos about Libya from Mr. Blumenthal, many of which were

passed on to her aides.

The

men had little experience in Libya. Exactly how Mr. White was to

procure leads in Libya is unclear. He spent much of his career as an

executive at the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum, and had raised

money for politicians, businesses and charities. His biography

also describes Mr. White as a consultant for Aquahydrate, a

bottled-water company whose backers include Ron Burkle, the billionaire

investor who had been a close friend of the Clintons.

“We

were thinking, ‘O.K., Qaddafi is dead, or about to be, and there’s

opportunities,’ ” Mr. White said in a brief telephone interview. He

added, “We thought, ‘Let’s try to see who we know there.’ ”

Mr.

White declined to answer follow-up questions about what role Mr.

Blumenthal was playing in the business venture. But Mr. Grange described

Mr. Blumenthal as an adviser to Mr. White’s company, along with two

other associates: Tyler Drumheller, a colorful former Central

Intelligence Agency official, and Cody Shearer, a longtime Clinton

friend.

“I just know that he was working with the team to work on business development,” Mr. Grange said of Mr. Blumenthal.

In

the spring of 2011, Mr. Blumenthal, Mr. Drumheller and Mr. Shearer were

helping plan what was to be Mr. Grange’s first trip to Libya, according

to emails stolen by a Romanian hacker and published by Gawker and ProPublica in March.

Mr. Blumenthal said he had been advised not to comment on the

correspondence because the theft remained under investigation by the

F.B.I.

In

August, Mr. Grange signed a memorandum of understanding with two senior

officials in the Libyan transitional government to provide

“humanitarian assistance, medical services and disaster mitigation,”

along with helping to train a new national police force.

The

agreement fell apart, Mr. Grange said, but the partners continued to

seek other projects in Libya, including a proposal to create the

floating hospitals to treat the country’s war wounded. But doing

business there proved difficult: Some Libyan leaders were wary about

working with Western companies, while the contractors could not figure

out whom to make deals with.

“It

was just so factionalized over there,” Mr. Grange said. “You never knew

who to believe or trust, or know who was in charge of what.”

Even

as their plans sputtered, Mr. Blumenthal continued to draw on the

business associates for information about Libya as he shaped his memos

to Mrs. Clinton. Sometimes the two realms became blurred.

In

January 2012, for example, Mr. Blumenthal sent Mrs. Clinton a memo

describing efforts by the new Libyan prime minister to stabilize his

fragile government by bringing in advisers with experience dealing with

Western companies and governments.

Among

“the most influential of this group,” Mr. Blumenthal wrote, was a man

named Najib Obeida, who worked at the fledgling Libyan stock exchange.

Mrs. Clinton had the memo forwarded to her senior State Department

staff.

What

Mr. Blumenthal did not mention was that Mr. Obeida was one of the

Libyan officials Mr. Grange and his partners hoped would finance the

humanitarian projects. The day before Mr. Blumenthal emailed Mrs.

Clinton, Mr. Grange wrote to a senior Clinton aide at the State

Department to introduce the venture with Mr. Obeida in Libya and seek an

audience with the United States ambassador there. Mr. Grange said he

had not received a reply.

Mr.

Blumenthal sent Mrs. Clinton at least 25 memos about Libya in 2011 and

2012, many describing elaborate intrigues among various foreign

governments and rebel factions.

Mrs.

Clinton circulated them, frequently forwarding them to Jake Sullivan,

her well-regarded deputy chief of staff, and requesting that he

distribute them to other State Department officials. Mr. Sullivan often

sent the memos to senior officials in Libya, including the ambassador,

J. Christopher Stevens, who was killed in the 2012 attacks in Benghazi.

In

many cases, Mr. Sullivan would paste the text from the memos into an

email and tell the other State Department officials that they had come

from an anonymous “contact” of Mrs. Clinton.

Some

of Mr. Blumenthal’s memos urged Mrs. Clinton to consider rumors that

other American diplomats knew at the time to be false. Not infrequently,

Mrs. Clinton’s subordinates replied to the memos with polite

skepticism.

In

April 2012, Mr. Stevens took issue with a Blumenthal memo raising the

prospect that the Libyan branch of the Muslim Brotherhood was poised to

make gains in the coming parliamentary elections. The Brotherhood fared

poorly in the voting.

Another

American diplomat read the memo, noting that Mrs. Clinton’s source

appeared to have confused Libyan politicians with the same surname.

Mrs.

Clinton herself sometimes seemed skeptical. After reading a March 2012

memo from Mr. Blumenthal, describing a plan by French and British

intelligence officials to encourage tribal leaders in eastern Libya to

declare a “semiautonomous” zone there, Mrs. Clinton wrote to Mr.

Sullivan, “This one strains credulity.”

Mr. Sullivan agreed, telling Mrs. Clinton, “It seems like a thin conspiracy theory.”

But

the skepticism did not seem to sour Mrs. Clinton on Mr. Blumenthal. She

continued to forward Mr. Blumenthal’s memos, often appending a note:

“Useful insight” or “We should get this around asap.”

In

an August 2012 memo, Mr. Blumenthal described the new president of

Libya, Mohamed Magariaf, as someone who would “seek a discrete

relationship with Israel” and had “many common friends and associates

with the leaders of Israel.”

“If true, this is encouraging,” Mrs. Clinton wrote to Mr. Sullivan. “Should consider passing to Israelis.”

The

emails suggest that Mr. Blumenthal’s direct line to Mrs. Clinton

circumvented the elaborate procedures established by the federal

government to ensure that high-level officials are provided with vetted

assessments of available intelligence.

Former

intelligence officials said it was not uncommon for top officials,

including secretaries of state, to look outside the intelligence

bureaucracy for information and advice. But Paul R. Pillar, a former

C.I.A. official who is now a researcher at the Center for Security

Studies at Georgetown University, said Mr. Blumenthal’s dispatches went

beyond that sort of informal channel, aping the style of official

government intelligence reports but without assessments of the motives

of sources.

“The

sourcing is pretty sloppy,” Mr. Pillar added, “in a way that would

never pass muster if it were the work of a reports officer at a U.S.

intelligence agency.”

No comments:

Post a Comment